Canada Gazette, Part I, Volume 151, Number 9: Regulations Amending the Heavy-duty Vehicle and Engine Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations and Other Regulations Made Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999

March 4, 2017

Statutory authority

Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999

Sponsoring departmentDepartment of the Environment

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: Emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) are contributing to a global warming trend that is associated with long-term climate change. In 2014, on-road heavy-duty vehicles were the source of about 8% of total GHG emissions in Canada. The annual amount of GHGs emitted by these vehicles in Canada doubled between 1990 and 2014, from 28 to 56 megatonnes (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) per year. In 2013, Canada began regulating GHG emissions from the on-road heavy-duty vehicle sector; however, without additional action, annual GHG emissions from freight transport, the majority of which come from heavy-duty vehicles, are projected to continue to increase and surpass annual GHG emissions from passenger transport by 2030.

Description: The proposed Regulations Amending the Heavy-duty Vehicle and Engine Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations and Other Regulations Made Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (the proposed Amendments) would introduce more stringent GHG emission standards that begin with the 2021 model year for on-road heavy-duty vehicles and engines. Further, the proposed Amendments introduce new GHG emission standards that would apply to trailers hauled by on-road transport tractors for which the manufacture is completed on or after January 1, 2018, starting with model year 2018 trailers. These emission standards for heavy-duty vehicles, engines and trailers would increase in stringency every three model years to the 2027 model year and maintain full stringency thereafter. The proposed Amendments would also amend two other regulations made under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 to ensure consistency with existing on-road vehicle and engine emission regulations and maintain alignment with U.S. regulatory provisions.

Cost-benefit statement: The proposed Amendments are estimated to lead to CO2e emission reductions of approximately 41 Mt from heavy-duty vehicles (including engines and trailers) produced in model years 2018 to 2029 (MY2018-2029), and to CO2e emission reductions of about 3 Mt from all heavy-duty vehicles in 2030. The total costs associated with the proposed Amendments for MY2018-2029 vehicles are projected to be $4.8 billion, largely due to additional costs of about $4.1 billion for the technologies that are expected to be adopted to meet the more stringent GHG emission standards for these vehicles. The total benefits are estimated at $13.6 billion, mostly due to fuel savings of about $10.3 billion, and GHG emission reductions and increased travel opportunities valued each at around $1.5 billion. Over the portion of the lifetime operation of MY2018-2029 vehicles that occurs during the 2018–2050 period, the net benefits of the proposed Amendments are estimated to be $8.8 billion.

“One-for-One” Rule and small business lens: The proposed Amendments would add trailers used with transport tractors into the regulatory framework. Canadian companies that manufacture or import trailers would be faced with new reporting obligations. The proposed Amendments would also lead to minor reductions in reporting burden for small volume companies that manufacture or import heavy-duty engines. The net annualized administrative costs introduced are projected to be approximately $25,000, or $130 per company.

The proposed Amendments would have an effect on about 175 companies that manufacture or import small volumes of heavy-duty engines and trailers for sale in Canada, many of which are small businesses. A flexible regulatory option that incorporates provisions tailored specifically to small volume companies has been selected. Relative to a non-flexible regulatory option, this option would yield annualized cost savings of about $1.7 million, or $10,000 per small volume company.

Domestic and international coordination and cooperation: The proposed Amendments would build on the history of collaboration achieved under the Canada–United States Air Quality Agreement in relation to the development of aligned vehicle and engine emission regulations and their coordinated implementation. In March 2016, Canada committed in the United States–Canada Joint Statement on Climate, Energy, and Arctic Leadership to implement a second phase of aligned GHG emission standards for on-road heavy-duty vehicles. The proposed Amendments are an important step towards this implementation and would contribute to Canada's international commitments made under the Paris Agreement.

Background

Since 2003, the Canadian Department of the Environment (the Department) has introduced a range of vehicle and engine emission regulations in alignment with the corresponding standards of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA), pursuant to the Canada–United States Air Quality Agreement. In 2011, the Canada–United States Regulatory Cooperation Council was established with a goal of enhancing the alignment of regulatory approaches between Canada and the United States in a broad range of areas, including vehicle emissions.

The Heavy-duty Vehicle and Engine Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations (the Regulations), made under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA), were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, on March 13, 2013. The objective of the Regulations is to reduce GHG emissions by establishing performance-based emission standards for heavy-duty vehicles and engines in alignment with the corresponding emission standards established by the U.S. EPA.

The Regulations apply to companies that manufacture or import new on-road heavy-duty vehicles and engines for sale in Canada. The GHG emission standards in the Regulations apply to vehicles and engines of the 2014 and later model years and reach full stringency with model year 2018. The Regulations apply to the entire range of on-road heavy-duty vehicles, from full-size pick-up trucks and vans to transport tractors manufactured primarily for hauling trailers, including a wide variety of specialized (vocational) vehicles, such as school, transit and intercity buses, and freight, delivery, service, cement, garbage and dump trucks.

In October 2014, a notice of intent was published in the Canada Gazette, Part I, announcing the Government of Canada's intention to develop proposed standards to further reduce GHG emissions from heavy-duty vehicles and engines in alignment with those of the United States. During consultations with stakeholders following the publication of the notice of intent, the Department confirmed that proposed regulatory amendments would build on the Regulations and would take specific implications for the on-road heavy-duty vehicle sector in Canada into consideration.

On October 25, 2016, the Government of the United States published its final rule concerning a second phase of GHG emission and fuel efficiency standards for heavy-duty vehicles, engines and trailers (the Phase 2 standards). (see footnote 1) These Phase 2 standards, which will be phased in gradually, reaching full stringency with model year 2027, will build upon the existing standards that are being phased in over model years 2014 to 2018; standards will also be introduced for trailers hauled by transport tractors, as trailer design has an impact on the GHG emissions and fuel consumption of the vehicles hauling them.

Recent policy context

At the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) conference in December 2015, the international community, including Canada, concluded the Paris Agreement, an accord intended to reduce GHG emissions to limit the rise in global average temperature to less than two degrees Celsius (2°C) and to pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. As part of its commitments made under the Paris Agreement, Canada pledged to reduce national GHG emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030.

In March 2016, First Ministers met in Vancouver, British Columbia, and agreed to build on the momentum of the Paris Agreement by developing a concrete plan to achieve Canada's international commitments through a pan-Canadian framework on clean growth and climate change.

Later in March 2016, Canada and the United States issued the United States–Canada Joint Statement on Climate, Energy and Arctic Leadership and resolved to work together to meet their respective commitments under the Paris Agreement. (see footnote 2) Recognizing the excellent collaboration between the two countries to establish world-class, aligned regulations and programs to reduce GHG and air pollutant emissions from on-road vehicles, Canada and the United States reaffirmed their commitment to continue this strong collaboration towards the finalization and implementation of a second phase of aligned GHG emission standards for heavy-duty vehicles.

Issues

The Government of Canada is committed to reducing GHG emissions to help limit global warming and the effects of climate change. The combustion of fuels for road transportation is an important source of such emissions. In 2014, the GHG emissions in Canada from road transportation sources totalled 171 megatonnes (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). Approximately 23% of total GHG emissions in the Canadian economy came from the transportation sector, making it the economic sector with the second-largest share of such emissions in Canada. (see footnote 3) Heavy-duty vehicles accounted for about 8% of total GHG emissions in Canada. The latest historical emissions trends show that the annual amount of GHGs emitted by on-road heavy-duty vehicles in Canada doubled from 28 to 56 Mt of CO2e per year between 1990 and 2014 (Table 1). (see footnote 4)

| 1990 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 613 | 744 | 747 | 706 | 732 |

| Transportation sector | 129 | 156 | 171 | 173 | 171 |

| On-road heavy-duty vehicles | 28 | 39 | 50 | 55 | 56 |

In 2013, Canada began controlling GHG emissions from the on-road heavy-duty vehicle sector by means of the Regulations, which are expected to lead to decreases in the growth of GHG emissions from heavy-duty vehicles. However, if additional action is not taken by the Government of Canada, annual GHG emissions from freight transport, the majority of which come from heavy-duty vehicles, are currently projected by the Department to continue to increase and surpass annual GHG emissions from passenger transport by 2030. (see footnote 5)

Objectives

The objective of the proposed Amendments is to further reduce GHG emissions in Canada from new on-road heavy-duty vehicles, engines and trailers by establishing more stringent emission standards to help protect Canadians and the environment from the effects of climate change. Additionally, the proposed Amendments aim to maintain common Canada–United States GHG emission standards for heavy-duty vehicles, engines and trailers, and contribute to minimizing the overall regulatory burden for companies operating in the Canada–U.S. market.

Description

The proposed Amendments would modify the Regulations, which apply to on-road vehicles with a gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) above 3 856 kilograms (kg) [8 500 pounds (lb)], with the exception of medium-duty passenger vehicles (e.g. certain large passenger vans), which are defined in the On-Road Vehicle and Engine Emission Regulations and subject to the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations. (see footnote 6) The proposed Amendments would apply to any person or company manufacturing or importing new vehicles, engines or trailers for the purpose of sale in Canada.

New and more stringent emission standards

The proposed Amendments would introduce more stringent GHG emission standards for heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans, vocational vehicles, transport tractors, and heavy duty engines designed for vocational vehicles and tractors. The more stringent emission standards would begin with the 2021 model year and increase in stringency for most vehicle and engine types with model years 2024 and 2027. (see footnote 7) Further, the proposed Amendments would introduce new standards for GHG emissions that result from the operation of trailers used with transport tractors. (see footnote 8) These standards would apply to trailers for which the manufacture is completed on or after January 1, 2018, and would start with the 2018 model year and increase in stringency for most trailer types with model years 2021, 2024 and 2027. All of these GHG emission standards are primarily performance-based, expressed in grams emitted per unit of work, and would therefore provide companies with flexibility when choosing the methods and technologies to comply with them.

Heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans

The proposed Amendments would include more stringent standards for CO2 emissions from heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans, starting with model year 2021 vehicles. The emission standards would continue to be fleet average standards for all applicable vehicles of a company's fleet and determined based on a work factor value, which is a function of the payload and towing capacities, and the four-wheel drive capability, of the vehicles in the fleet. Vehicle emission performance would be measured using prescribed test cycles on a chassis dynamometer.

Vocational vehicles

The proposed Amendments would include more stringent standards for CO2 vehicle emissions from vocational vehicles, starting with model year 2021 vehicles. The emission performance of vocational vehicles would be assessed using an enhanced version of the Greenhouse Gas Emissions Model (GEM), a simulation model developed by the U.S. EPA. (see footnote 9)

The CO2 vehicle emission standards for vocational vehicles would vary based on the type of operation that applies (i.e. urban, regional or multi-purpose operation). Also, the proposed Amendments would include alternative emission standards for certain classes of vocational vehicles with specific applications, such as emergency vehicles, motor homes, coach and school buses, waste collection vehicles, and concrete mixers. Finally, a leakage standard for refrigerants from air conditioning systems in vocational vehicles of the 2021 and later model years would be established, aligning it with the current leakage standard in the Regulations for heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans, and tractors.

Tractors

The proposed Amendments would include more stringent CO2 vehicle emission standards aligned with the corresponding U.S. standards for transport tractors with a gross combined weight rating (GCWR) below 54 431 kg (120 000 lb), starting with model year 2021 vehicles. (see footnote 10) As described below, the proposed Amendments would also establish new CO2 vehicle emission standards for two sets of transport tractors with greater GCWRs that are aligned with similar standards in the United States while taking Canadian-specific considerations into account. The emission performance of all transport tractors would be assessed using an enhanced version of GEM.

Heavy line-haul tractors

Greater weights are permitted on Canadian roads by provincial and territorial jurisdictions compared to the weights allowed on U.S. roads. To account for this context, the proposed Amendments would establish new CO2 vehicle emission standards, starting with the 2021 model year, for a set of transport tractors with a GCWR of at least 54 431 kg (120 000 lb) and below 63 503 kg (140 000 lb), which are referred to as “heavy line-haul tractors.” Heavy line-haul tractors are designed for on-road applications that mainly involve hauling higher payloads over long distances on highways. The emission standards for heavy line-haul tractors would be less stringent than the standards for tractors with a GCWR below 54 431 kg (120 000 lb). These standards would take powertrain characteristics required for tractors with higher payload capacities into consideration and, at the same time, reflect improvements in technologies reducing GHG emissions that are appropriate for highway hauling applications in Canada, such as technologies that reduce aerodynamic drag and main engine idling. The emission standards for heavy line-haul tractors in Canada would be aligned with corresponding optional standards in the United States.

Heavy-haul tractors

The proposed Amendments would establish new CO2 vehicle emission standards, starting with the 2021 model year, for a set of transport tractors with a GCWR of 63 503 kg (140 000 lb) or more, which are defined as “heavy-haul tractors.” Heavy-haul tractors are designed for on-road specialty applications that typically involve hauling very high payloads over short distances. The emission standards for heavy-haul tractors in Canada would be less stringent than those for tractors with a GCWR below 63 503 kg (140 000 lb) and would be aligned with the corresponding standards in the United States. Given that greater weights are permitted on Canadian roads relative to the United States, and that standards are proposed for heavy line-haul tractors to account for this context, the proposed Amendments would introduce a Canadian-specific definition of a heavy-haul tractor. A heavy-haul tractor in Canada would be defined as any tractor with a GCWR of 63 503 kg (140 000 lb) or more, whereas a heavy-haul tractor in the United States is defined as any tractor with a GCWR of at least 54 431 kg (120 000 lb).

Auxiliary power units

Important GHG emission reductions could be realized from the operation of auxiliary power units (APUs) installed in transport tractors as an alternative to main engine idling. However, diesel-powered APUs are sources of particulate matter emissions; consequently, an increase in such emissions is likely to result from an increased use of APUs powered by diesel. For these reasons, the proposed Amendments would modify the On-Road Vehicle and Engine Emission Regulations to include standards for particulate matter emissions from tractors equipped with APUs.

Heavy-duty engines

The proposed Amendments would include more stringent standards for CO2 emissions from compression-ignition (diesel) engines designed for vocational vehicles and tractors, starting with model year 2021 engines. Also, the proposed Amendments would introduce alternative emission standards for some engines of the 2024 to 2026 model years. Specifically, a company that chooses to have its model year 2020 engines designed for vehicles with a GVWR above 8 845 kg (19 500 lb) conform to the standards applicable to model year 2021 engines would be allowed to comply with alternative emission standards with a lower level of stringency applicable to engines of model years 2024 to 2026. Engine emission performance would be measured using prescribed test cycles on an engine dynamometer.

Trailers

The proposed Amendments would introduce new standards for CO2 emissions attributable to trailers hauled by transport tractors. Standards for box van trailers would be set according to the type of box van trailer and take into account technologies installed on trailers to reduce GHG emissions, such as devices to reduce aerodynamic drag, low rolling resistance tires, lightweight components, and tire pressure monitoring and automatic tire inflation systems. (see footnote 11) The emission performance of box van trailers would be assessed using a prescribed equation with a set of coefficients for calculating CO2 emissions related to each of the technologies installed on trailers to reduce emissions. Also, the proposed Amendments would introduce design-based standards for non-box trailers and box van trailers that cannot be equipped with devices to reduce aerodynamic drag due to their distinct applications. The design-based standards would require that these trailers be equipped with low rolling resistance tires, and tire pressure monitoring or automatic tire inflation systems.

Compliance flexibilities

The proposed Amendments would offer several flexibilities to support compliance with the emission standards, which are described below.

CO2 emission credit system for heavy-duty vehicles and engines

The proposed Amendments would extend the existing system of CO2 emission credits to help meet overall environmental objectives in a manner that provides companies with compliance flexibility. The system would continue to allow companies to generate, bank and trade emission credits for heavy-duty vehicles and engines in the same manner as in the Regulations. (see footnote 12) The proposed Amendments would allow a company to be eligible for additional emission credits by means of enhanced credit multipliers for plug-in hybrid, electric or fuel cell vehicles of the 2021 to 2027 model years, if the company chooses to participate in the CO2 emission credit system. The proposed Amendments would also continue to allow a company to be eligible for additional emission credits, if the company incorporates innovative technologies into its vehicles or engines which generate reductions in CO2 emissions that cannot be measured during prescribed emission testing or through the use of GEM.

Exemptions for small volume companies

Under the Regulations, companies have the option to exempt their vocational vehicles and tractors of a given model year from complying with the CO2 vehicle emission standards, provided that they manufactured or imported fewer than 200 vocational vehicles and tractors for sale in Canada in 2011, and that they manufacture or import fewer than 200 vocational vehicles and tractors for sale in Canada on average over the three most recent consecutive model years. The proposed Amendments would simplify the requirements that companies manufacturing or importing vocational vehicles and tractors must satisfy to qualify for the existing exemption for small volume companies. The exemption from emission standards would also be expanded to include the engines installed in exempt vocational vehicles and tractors. Further, the proposed Amendments would contain a temporary, one-year exemption from the CO2 emission standards for small volume companies that manufacture or import fewer than 100 trailers for sale in Canada in 2018.

Transitional exemption for trailers

The proposed Amendments would incorporate a transitional exemption for companies that manufacture or import trailers of the 2018 to 2026 model years. This transitional exemption would allow a company to exempt a number of box van and non-box trailers from the CO2 emission standards under the two following conditions: (i) the number of box van or non-box trailers exempt must not exceed 20% of the total number of box van or non-box trailers that the company manufactures or imports for sale in Canada for a given model year; and (ii) this number must be lower than 25 in the case of box van trailers, and lower than 20 in the case of non-box trailers, for a given model year.

Fleet average standards for CO2 emissions attributable to box van trailers

Starting with the 2027 model year, the proposed Amendments would provide a company that manufactures or imports box van trailers with the flexibility of meeting a fleet average standard for CO2 emissions, for each of its fleets of trailers of a given model year, to help reduce the compliance burden associated with the new emission standards applicable to box van trailers.

Reporting requirements

The proposed Amendments would expand the scope of the annual end of model year report to manufacturers and importers of trailers used with transport tractors of the 2018 and later model years in Canada. The information that would be required to be included in this report concerning trailers has been streamlined to minimize additional administrative burden.

Additional amendments to other regulations under CEPA

Additional amendments are proposed to ensure consistency within the Department's suite of on-road vehicle and engine emission regulations and to maintain alignment with U.S. regulatory provisions. In particular, to maintain alignment with the United States, the proposed Amendments would modify the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations to incorporate a provision that allows companies to be eligible for an expanded CO2 emission allowance for their full-size hybrid pick-up trucks of the 2017 to 2021 model years. Also, the proposed Amendments would modify the On-Road Vehicle and Engine Emission Regulations to update references to the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, address discrepancies between the English and French versions, improve the clarity of the regulatory text, and enhance alignment with the U.S. regulatory provisions.

Regulatory and non-regulatory options considered

The Government of Canada currently regulates emissions from heavy-duty vehicles and engines under CEPA, and considered maintaining the regulatory status quo or updating the regulatory requirements to achieve stringent aligned Canada–U.S. standards.

Status quo approach

The Regulations establish the Phase 1 standards for heavy-duty vehicles and engines that begin in the 2014 model year and increase in stringency to the 2018 model year. In the absence of the proposed Amendments, the 2018 model year standards would apply to all heavy-duty vehicles and engines of the 2019 and later model years, and GHG emissions attributable to trailers would remain unregulated.

Without the proposed Amendments, vehicles and engines compliant with the Phase 1 standards (but not with the more stringent Phase 2 standards) and unregulated trailers would be allowed to be manufactured and imported for sale in Canada. Consequently, the additional GHG emission reductions and other benefits that are associated with maintaining alignment with the U.S. standards for vehicles, engines and trailers would not be fully realized. Further, the vehicle and trailer manufacturing sectors in Canada and the United States are highly integrated. Under a status quo approach, regulatory misalignment would create a non-level playing field for manufacturers and importers in Canada and the United States. It would allow Canadian companies that manufacture or import less expensive heavy-duty vehicles and trailers that do not meet the Phase 2 standards to place competitive pressure on other companies operating in Canada that would comply with the Phase 2 standards. For these reasons, this option was rejected.

Regulatory approach — Maintaining Canada–U.S. alignment

The vehicle and trailer manufacturing sectors in Canada and the United States are highly integrated, and there is a long history of collaboration in working towards the alignment of emission standards. The implementation of common Canada–U.S. standards for manufacturers and importers would provide regulatory certainty to facilitate investment decisions and minimize regulatory burden by allowing the use of common information, data and emission testing results to demonstrate compliance. Maintaining regulatory alignment with the Phase 2 standards is the option that is being proposed. This option would deliver important GHG emission reductions while preserving the competitiveness of the heavy-duty vehicle and trailer manufacturing sectors in Canada.

Benefits and costs

An analysis of the incremental impacts was conducted using business-as-usual (BAU) and regulatory scenarios. The costs and benefits of the proposed Amendments have been assessed in accordance with the Canadian Cost-Benefit Analysis Guide published by the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS). (see footnote 13)

The expected impacts of the proposed Amendments are presented in the logic model (Figure 1) below. Compliance with the stricter limits in the proposed Amendments for GHG emissions from heavy-duty vehicles would lead to important GHG emission reductions and fuel savings by means of more effective vehicle emission technologies. These fuel savings are anticipated to result in reduced refuelling time for vehicle operators and additional opportunities for vehicle operators to transport goods and provide services. Compliance with the proposed Amendments would also result in health and environmental benefits for Canadians through improvements in air quality.

Figure 1: Logic model for the analysis of the proposed Amendments

Analytical framework

Impacts are analyzed in terms of changes to vehicle technologies, emissions, and associated costs and benefits, in the regulatory scenario compared to the BAU scenario. The incremental impacts are the differences between the estimated levels of technologies and emissions, and the differences between the associated costs and benefits, in the two scenarios. To the extent possible, benefits and costs are quantified and monetized, and the monetized impacts are expressed in 2015 Canadian dollars. The first year of regulatory implementation is 2018. The analysis uses 2016 as the present value base year and ends in 2050. Unless otherwise indicated, the monetized impacts are analyzed in present value terms, applying a 3% discount rate for future years, in accordance with TBS guidance for environmental and health regulatory analyses. Other identified impacts have been considered qualitatively.

The Department conducted two distinct types of analysis that show the projected impacts of the Phase 2 standards from different perspectives. First, a model year analysis was conducted to estimate the costs and benefits associated with the operation of MY2018-2029 Phase 2 vehicles that are expected to be produced within the time frame of regulatory implementation. (see footnote 14) In addition, an alternative calendar year analysis was conducted to provide estimates of the annual impacts attributable to all Phase 2 vehicles over the analytical time frame, including the costs and benefits resulting from Phase 2 vehicles of the 2030 and later model years (i.e. the impacts associated with the ongoing implementation of the Phase 2 standards at full stringency). Results from both types of analysis are presented below.

The BAU scenario assumes that emission rates corresponding to the Phase 1 standards in the Regulations for model year 2018 (MY2018) engines, heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans, vocational vehicles, and transport tractors would be extended indefinitely into the future with no change in stringency. (see footnote 15) Further, the BAU scenario assumes that standards would not be adopted for trailers used with transport tractors. (see footnote 16)

The regulatory scenario assumes that new GHG emission standards would be introduced for trailers used with transport tractors beginning in MY2018 and more stringent GHG emission standards would be introduced for the currently regulated categories of vehicles (heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans, vocational vehicles, and transport tractors) and engines beginning in MY2021. These proposed emission standards, which are collectively referred to as the “Phase 2 standards,” would increase in stringency every three model years to MY2027 and maintain full stringency thereafter. Overall emission reductions are expected to increase over time as vehicles and trailers that are compliant with the Phase 2 standards become a larger percentage of the in-use fleet. It is projected that most on-road heavy-duty vehicles in Canada would be compliant with these standards by 2050 in the regulatory scenario.

In order to assess the impacts of the proposed Amendments, it was necessary to obtain Canadian estimates of future vehicle sales, fuel prices and monetary values for GHG emission reductions; to identify the technologies that manufacturers would likely adopt and the costs they would carry; and to then model future vehicle emissions, fuel consumption and distance travelled, with and without the proposed standards. The key sources of data that were used to complete these tasks, including the proposed U.S. Phase 2 rule and its associated regulatory impact analysis, are described throughout this analysis. (see footnote 17)

The emission standards from the final U.S. Phase 2 rule have been incorporated into the proposed Amendments. However, since the Department's modelling of Canadian costs and benefits was conducted prior to the publication of the final U.S. rule, the following impact analysis considers the emission standards proposed by the U.S. EPA in July 2015 in a Canadian context and does not take into account changes made in the final U.S. rule. Relative to the proposed U.S. Phase 2 rule, the final rule includes CO2 emission standards that are more stringent for diesel engines and better tailored to vehicle application for vocational vehicles, as well as new standards for particulate matter emissions from APUs. The Department plans on updating its modelling to reflect the costs and benefits of these provisions in a Canadian context in the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement published with the final Amendments in the Canada Gazette, Part II. It is anticipated that both cost and benefit estimates would increase as a result of these modelling updates, and that overall the regulatory proposal would lead to net benefits for Canadians.

Costs

The analysis of costs assumes full compliance with the Phase 2 standards proposed by the U.S. EPA in July 2015 (the “proposed Phase 2 standards”), which would impose upfront vehicle technology costs and ongoing tire maintenance costs on industry stakeholders. Compliance would lead to fuel savings, thereby encouraging additional driving. In turn, this “rebound-effect” driving is expected to lead to increases in accidents, congestion and noise caused by heavy-duty vehicles. To help ensure that compliance with the standards is maximized, there would also be some business administrative and government costs.

Vehicle technology and tire maintenance costs

The proposed Phase 2 standards were modelled to apply to all newly manufactured or imported trailers of the 2018 and later model years hauled by on-road transport tractors, and to all newly manufactured or imported on-road heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans, vocational vehicles, tractors, and the engines used to power vocational vehicles and tractors, of the 2021 and later model years (“Phase 2 vehicles”). Phase 2 vehicles can be powered by gasoline, diesel, electricity, compressed natural gas, liquefied petroleum gas, or a combination of energy sources. Nonetheless, it is anticipated that Phase 2 vehicles would be predominately powered by gasoline and diesel engines. Consequently, this analysis assumes that all Phase 2 vehicles are powered by gasoline and diesel engines, including hybrid electric engine types.

Multiple Canadian sources of information on historical vehicle sales and registration, and vehicle sales forecasts, were used as inputs into the Motor Vehicle Emission Simulator (MOVES) and processed for forecasting, generating projected sales of heavy-duty vehicles for use in Canada for each required vehicle class and model year. These projections are summarized in Table 2 in the form of average sales for four periods covering model years 2018 to 2029. Future sales of trailers for use in Canada were projected using the historical sales ratio of trailers to tractors that was estimated to be about 1.6 to 1 in a study conducted for the Department by the International Council on Clean Transportation in 2016 (the 2016 ICCT study).

| Engine Fuel Type | Vehicle Category | MYs 2018-2020 | MYs 2021-2023 | MYs 2024-2026 | MYs 2027-2029 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel | Tractors | 25 431 | 26 070 | 24 919 | 25 650 |

| Vocational vehicles | 28 035 | 28 892 | 28 079 | 29 619 | |

| Heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans | 24 743 | 25 033 | 23 666 | 23 583 | |

| Gasoline | All categories | 51 800 | 52 518 | 49 767 | 50 009 |

| No engine | Trailers | 40 722 | 41 745 | 39 900 | 41 071 |

Note: The estimated sales ratio of trailers to tractors of 1.6 to 1 from the 2016 ICCT study was used to project trailer sales.

Phase 2 vehicles, engines and trailers would be required to comply with GHG emission standards that increase in stringency from model years 2018 to 2027 for trailers, and from model years 2021 to 2027 for vehicles and engines, as previously described. Given that these proposed standards are primarily performance-based standards, manufacturers and importers in most cases would be free to choose what technology packages to adopt in order to comply with the standards and achieve emission reductions. However, this would not be the case for non-aerodynamic and non-box trailers, for which design-based standards are being introduced, requiring these trailers to be equipped with lower rolling resistance tires, and automatic tire inflation or tire pressure monitoring systems.

The proposed Phase 2 standards were modelled to align with the proposed GHG emission standards of the U.S. EPA for the 2018 and later model years, which would provide manufacturers with a common set of Canada–U.S. standards for heavy-duty vehicles, engines and trailers. As a result, the analysis assumes that manufacturers supplying the Canadian and American markets would likely adopt similar technologies to meet these emission standards. Table 3 presents a list of technologies that manufacturers are likely to choose to comply with the proposed Phase 2 standards.

| Category of Vehicle | Vehicle Technology | |

|---|---|---|

| Tractors |

|

|

| Trailers |

|

|

| Vocational vehicles |

|

|

| Heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans |

|

|

Based on engineering and market analyses, the U.S. EPA determined technology packages that were most likely to be adopted from existing and anticipated sets of vehicle, engine and trailer technologies. Next, the U.S. EPA projected the rates of adoption for these technology packages that would be necessary to comply with the Phase 2 standards, and estimated the redesign and application costs per vehicle for those technology packages. The U.S. EPA's assessment of technologies that would be available for each vehicle, engine and trailer category, and the estimates of their relative effectiveness and costs, were guided by published research and independent assessments. For each vehicle, engine and trailer category, technologies that could be applied practically and cost-effectively have been identified.

The availability and increase in market penetration rates of technologies have been assessed by the U.S. EPA, together with effectiveness and costs, for each model year from 2018 to 2027. The technology costs are incremental to the costs in the BAU scenario (Phase 1). In the regulatory scenario, technologies and compliance options are applied to vehicles, engines and trailers in order for companies to meet the standards. The estimated incremental cost per vehicle or trailer is calculated on this basis. Given the integration of the Canada–U.S. vehicle and trailer manufacturing sectors, and the alignment with the proposed Phase 2 standards, the same technology choices and adoption rates assumed by the U.S. EPA are used in this analysis. This leads to similar costs per vehicle, adjusted for inflation and exchange rates, as those calculated in the analysis of the proposed U.S. Phase 2 rule.

The Department has also estimated increased maintenance costs associated with the installation of lower rolling resistance tires. It is expected that, when replaced, the lower rolling resistance tires would be replaced by equivalent performing tires throughout the lifetime of the vehicle or trailer. Therefore, the incremental increases in costs for lower rolling resistance tires would be carried throughout the lifetime of the vehicle or trailer at intervals consistent with current tire replacement intervals. Tire replacement intervals were chosen for each vehicle category in the Canadian heavy-duty fleet, based on total distance travelled per vehicle and approximations of the total number of tire replacements per vehicle, as follows: 75 000 kilometres (km) for heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans, with an average of over two tire replacements per vehicle lifetime; 100 000 km for vocational vehicles, with an average of about nine tire replacements per vehicle lifetime; and 250 000 km for tractor-trailers, with an average of over five tire replacements per vehicle lifetime. The same maintenance costs assumed by the U.S. EPA in its analysis of the proposed Phase 2 rule, adjusted for inflation and exchange rates, are applied in this analysis at the selected tire replacement intervals.

Table 4 presents the estimates of the vehicle technology and tire maintenance costs carried by Canadian manufacturers and importers due to the adoption of the Phase 2 standards for MY2018-2029 vehicles.

| MYs 2018-2020 | MYs 2021-2023 | MYs 2024-2026 | MYs 2027-2029 | MYs 2018-2029 (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle technology costs | |||||

| Tractor-trailers | 98 | 677 | 857 | 955 | 2,587 |

| Vocational vehicles | 0 | 198 | 276 | 487 | 961 |

| Heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans | 0 | 137 | 218 | 240 | 594 |

| Total | 98 | 1,011 | 1,351 | 1,682 | 4,142 |

| Tire maintenance costs | |||||

| Tractor-trailers | 25 | 34 | 29 | 26 | 114 |

| Vocational vehicles | 0 | 7 | 14 | 15 | 36 |

| Heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Total | 25 | 43 | 45 | 44 | 156 |

Note: Costs are discounted to present value at 3% per year. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Costs due to accidents, congestion and noise

In the context of heavy-duty vehicles, increased vehicle fuel efficiency is expected to lead to more intensive vehicle use. This increase in vehicle use in response to lower vehicle operating costs is referred to as the “rebound effect,” and is measured in vehicle-kilometres (distance) travelled. The rebound effect is expected to lead to more accidents, congestion and noise.

The rebound effect in this analysis refers to the fraction of gasoline and diesel savings expected to result from an increase in fuel efficiency that is offset by additional vehicle use. Overall, increases in annual distance travelled per vehicle in the regulatory scenario, in response to total vehicle operating cost savings due to fuel savings, are estimated to be small, averaging around 0.8% over the 2018–2050 period.

There are no identified Canadian estimates of heavy-duty vehicle costs per kilometre for accidents, congestion and noise. The Department used the central estimates from the analysis of the proposed U.S. Phase 2 rule for marginal accident, congestion and noise costs due to increases in vehicle distance travelled. The per-kilometre cost estimates were applied in this analysis to the Canadian estimates of distance travelled due to the rebound effect in order to obtain estimates of the overall value of accidents, congestion and noise for each vehicle category.

Table 5 presents the estimates of the accident, congestion and noise costs due to increases in distance travelled by MY2018-2029 vehicles over the 2018–2050 period.

| MYs 2018-2020 | MYs 2021-2023 | MYs 2024-2026 | MYs 2027-2029 | MYs 2018-2029 (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs due to accidents, congestion and noise | |||||

| Tractor-trailers | 53 | 56 | 49 | 46 | 205 |

| Vocational vehicles | 0 | 112 | 100 | 96 | 309 |

| Heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans | 0 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 37 |

| Total | 53 | 182 | 162 | 153 | 550 |

Note: Costs are discounted to present value at 3% per year. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Business administrative and government costs

The proposed Amendments would introduce incremental administrative costs for trailer manufacturers and importers, while reductions in administrative burden are expected for small volume companies that manufacture or import vocational vehicles and tractors. Business administrative costs are discussed in further detail in the section of this statement concerning the ‘“One-for-One” Rule.' The annualized business administrative costs are estimated to be approximately $36,000 per year (undiscounted).

As a result of the addition of the CO2 emission standards for trailers, there would be federal government costs for additional compliance promotion, enforcement activities and regulatory administration. The annualized government costs are estimated to be up to $275,000 per year (undiscounted). No incremental government costs related to ongoing administration, enforcement activities or emission verification operations for the categories of heavy-duty vehicles and engines that are currently subject to the Phase 1 standards are expected. The existing implementation strategy for executing the GHG regulatory program for MY2014-2018 heavy-duty vehicles and engines would be extended to vehicles and engines of the 2019 and later model years.

Calendar year analysis of costs

In the regulatory scenario, the Phase 2 standards would be phased in starting with MY2018, reach full stringency with MY2027, and maintain this level of stringency until 2050. A calendar year analysis was conducted to estimate the costs attributable to all Phase 2 vehicles from 2018 to 2050. From this perspective, the costs are estimated at $15.4 billion, largely due to the additional costs of the vehicle technologies expected to be adopted to meet the Phase 2 standards. Table 6 shows the breakdown of these costs for all heavy-duty vehicles in select years and over the 2018–2050 period.

| 2020 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 | 2018–2050 (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle technology costs | 31 | 536 | 462 | 381 | 13,867 |

| Tire maintenance costs | 2 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 345 |

| Costs due to accidents, congestion and noise | 4 | 39 | 49 | 49 | 1,215 |

| Total | 37 | 587 | 524 | 443 | 15,427 |

Note: Costs are discounted to present value at 3% per year. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Benefits

The Department adapted and employed the U.S. EPA's peer-reviewed MOVES model to estimate the impact of the proposed Phase 2 standards in a Canadian context. (see footnote 18) Key data for Canadian vehicle operating conditions, fuel properties and vehicle characteristics were incorporated into MOVES. Emission and fuel consumption estimates were modelled in MOVES annually for the BAU and regulatory scenarios from 2018 to 2050 at the national level.

For the BAU scenario, emissions from heavy-duty vehicles and engines of the 2014 and later model years were assumed to meet the existing Phase 1 emission standards. Fuel quality parameters were estimated from reporting data collected annually from fuel refiners and importers under several departmental regulations. Historical vehicle sales and registration data used for the Phase 1 regulatory analysis were complemented by a key dataset purchased by the Department from R.L. Polk & Company, covering the Canadian heavy-duty vehicle fleet up to 2013. Forecasts of future vehicle sales were informed by a study conducted for the Department by Environ in 2015, while estimates of historical sales of trailers were obtained from the 2016 ICCT study.

For the regulatory scenario, vehicle emission rates were assumed to meet the Phase 2 standards for the 2018 and later model years, with increasing stringency over model years 2018 to 2027, as previously described. Vehicle fleet composition and size were assumed to be the same in the BAU and regulatory scenarios. In terms of vehicle fleet activity, the Canadian analysis used the same rebound effect estimates as those employed by the U.S. EPA in the analysis of the proposed U.S. Phase 2 rule; specifically, 5% for tractors; 10% for heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans; and 15% for vocational vehicles. These rebound effect estimates were applied in MOVES to annual Canadian estimates of the baseline distance travelled by the vehicle fleet to project the increase in distance travelled attributable to the rebound effect in the regulatory scenario.

GHG emission reductions

The Regulations and proposed Amendments address emissions of three GHGs: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O). In order to comply with the Phase 2 standards, manufacturers are expected to adopt various technologies that would increase the fuel efficiency associated with the operation of on-road heavy-duty vehicles. As a result of this anticipated adoption of technologies improving fuel efficiency, the proposed Phase 2 standards would lead to significant gasoline and diesel savings for the owners and operators of on-road heavy-duty vehicles while generating important GHG emission reductions.

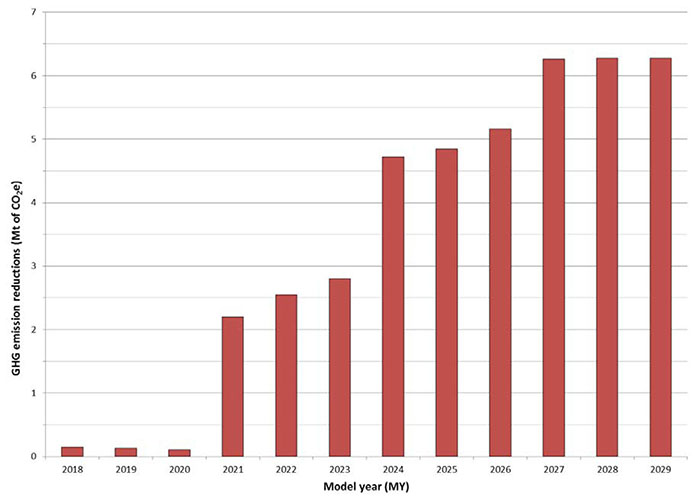

The Phase 2 standards are estimated to result in lifetime reductions of CO2e emissions for the cohort of vehicles in the model year analysis, increasing from 0.4 Mt for MY2018-2020 vehicles to 18.8 Mt for MY2027-2029 vehicles. (see footnote 19) The emission reductions from MY2018-2020 vehicles are fully attributable to the standards that would apply to MY2018-2020 trailers hauled by transport tractors. Overall, these standards are estimated to result in a cumulative reduction of around 41.5 Mt of CO2e emissions with respect to the portion of the lifetime operation of MY2018-2029 vehicles that occurs over the 2018–2050 period. The proposed Phase 2 standards would remain in full effect for vehicles of the 2030 and later model years. The average reduction in GHG emissions per model year during the lifetime operation of these vehicles would thus likely be similar to the average reduction of 6.3 Mt of CO2e emissions that have been estimated with respect to the lifetime operation of MY2029 Phase 2 vehicles that occurs over the 2018–2050 period.

Figure 2 presents the modelled trends in GHG emission reductions attributable to the Phase 2 standards with respect to the lifetime operation of MY2018-2029 heavy-duty vehicles over the 2018–2050 period. The increasing stringency of these standards, which occurs with model years 2021, 2024 and 2027, is clearly shown.

Figure 2: GHG emission reductions from MY2018-2029 Phase 2 vehicles over the 2018–2050 period

The estimated value of avoided damages from GHG emission reductions is based on the avoided climate change damages due to emissions of CO2, CH4 and N2O. The social cost of CO2, commonly referred to as the social cost of carbon, and the social costs of CH4 and N2O, are monetary measures of the global climate change damages expected from the atmospheric emissions in a given year of an additional tonne of CO2, CH4 and N2O, respectively. Alternatively, these social costs can be used to measure the value (benefits) of avoided damages from marginal decreases in emissions of CO2, CH4 and N2O. The central estimates of the social costs of CO2, CH4 and N2O have been recently updated and published by the Department. (see footnote 20) These central estimates are employed throughout this analysis to generate estimates of the value of the projected changes in emissions of these three GHGs.

The estimates of GHG emission reductions from MY2018-2029 Phase 2 vehicles are summarized in Table 7, along with the associated monetized benefits that have been calculated with the central estimates of the social costs of CO2, CH4 and N2O.

| MYs 2018-2020 | MYs 2021-2023 | MYs 2024-2026 | MYs 2027-2029 | MYs 2018-2029 (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHG emission reductions (Mt of CO2e) | |||||

| Tractor-trailers | 0.4 | 4.7 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 22.2 |

| Vocational vehicles | 0.0 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 4.5 | 8.4 |

| Heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans | 0.0 | 1.5 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 10.9 |

| Total | 0.4 | 7.5 | 14.7 | 18.8 | 41.5 |

| Benefits due to GHG emission reductions (millions of dollars) | |||||

| Tractor-trailers | 15 | 176 | 294 | 310 | 794 |

| Vocational vehicles | 0 | 49 | 92 | 155 | 296 |

| Heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans | 0 | 54 | 139 | 186 | 379 |

| Total | 15 | 278 | 525 | 650 | 1,468 |

Note: Benefits are discounted to present value at 3% per year. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Fuel savings

Manufacturers are expected to meet the proposed Phase 2 standards by adopting heavy-duty vehicle, engine and trailer technologies that reduce GHG emissions. Most of these technologies would achieve emission reductions by improving vehicle energy efficiency. MOVES was used to estimate these vehicle efficiency improvements due to technological improvements, and these energy savings were then converted to fuel savings and GHG emission reductions using standard conversion procedures.

For the cohort of vehicles in the model year analysis, technological improvements that are projected to be adopted to meet the Phase 2 standards would lead to fuel savings that increase from 0.1 billion litres for MY2018-2020 vehicles to 7.2 billion litres for MY2027-2029 vehicles. Similar to the GHG emission reductions from MY2018-2020 vehicles, fuel savings from these vehicles are fully attributable to the standards that would apply to MY2018-2020 trailers used with transport tractors. Altogether, the proposed standards are estimated to result in cumulative fuel savings of about 15.7 billion litres with respect to the portion of the lifetime operation of MY2018-2029 vehicles that occurs over the 2018–2050 period.

Fuel price forecasts for both gasoline and diesel were adopted from the Department's Energy-Emissions-Economy Model for Canada (E3MC) for the years 2016 to 2035. The E3MC model is an end-use model that incorporates current Canadian projections of energy supply, and of petroleum and natural gas prices, from the National Energy Board. (see footnote 21) It uses this data to generate energy demand forecasts that are primarily based on consumer-choice modelling and historical relationships between macroeconomic and fuel price variables. Fuel prices beyond 2035 were projected based on the average growth rate of fuel prices for the years 2020 to 2035 in the E3MC model.

Pre-tax gasoline and diesel prices were used to generate estimates of the benefits due to fuel savings from MY2018-2029 vehicles, which are summarized in Table 8. (see footnote 22)

| MYs 2018-2020 | MYs 2021-2023 | MYs 2024-2026 | MYs 2027-2029 | MYs 2018-2029 (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel savings (millions of litres) | |||||

| Tractor-trailers | 147 | 1,721 | 2,993 | 3,259 | 8,120 |

| Vocational vehicles | 0 | 603 | 1,612 | 2,216 | 4,431 |

| Heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans | 0 | 500 | 980 | 1,697 | 3,178 |

| Total | 147 | 2,824 | 5,585 | 7,173 | 15,729 |

| Benefits from fuel savings (millions of dollars) | |||||

| Tractor-trailers | 107 | 1,238 | 2,032 | 2,086 | 5,462 |

| Vocational vehicles | 0 | 355 | 658 | 1,072 | 2,085 |

| Heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans | 0 | 403 | 1,025 | 1,336 | 2,764 |

| Total | 107 | 1,996 | 3,714 | 4,493 | 10,311 |

Note: Fuel savings include reductions in both diesel and gasoline use, and are monetized using pre-tax fuel prices. Benefits are discounted to present value at 3% per year. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Since the projected fuel savings shown above should be more than enough on their own to motivate further GHG emission reductions, reasons that help explain why vehicle owners are not expected to fully respond to future fuel savings and adopt more efficient technologies in the absence of the proposed Amendments have been considered. To begin, comprehensive and reliable information on the effectiveness and efficiency of new technologies is not always available, and buyers may as a result be reluctant to purchase heavy-duty vehicles equipped with these new technologies. Further, if buyers are not directly responsible for future fuel costs, then there are reduced (or “split”) incentives for them to invest in vehicles with technologies that improve fuel efficiency. Buyers may also underestimate future fuel savings due to uncertainty regarding future fuel prices and the effectiveness of new technologies in reducing fuel consumption. Altogether, costly information, split incentives and uncertainty concerning future market conditions are expected to limit the adoption of new technologies in the absence of further government intervention.

Additional benefits related to fuel savings

In addition to directly reducing the fuel expenditures of owners and operators of on-road heavy-duty vehicles, improved fuel efficiencies would generate two additional effects. All else being equal, increased fuel efficiencies would lead to less time spent refuelling for operators, while these improved efficiencies and less time spent refuelling would yield increases in the distance travelled by heavy-duty vehicles which, in turn, would increase the opportunities to transport goods and provide services with these vehicles.

Fuel savings are expected to reduce refuelling frequency, which is a time-saving benefit for vehicle operators. The calculation of refuelling time savings uses the reduced number of litres of fuel consumed in a given year, for each of the main vehicle categories, and divides that value by fuel tank volume and refill amount to obtain the number of refills. This result is multiplied by the time taken per refill to determine the time saved in that year. The inputs used in this calculation were taken from the analysis of the proposed U.S. Phase 2 rule, with the wage rate estimates by vehicle type being converted to 2015 Canadian dollars. Using these inputs, the benefits of refuelling time savings are expected to be $372 million for the MY2018-2029 fleet (Table 9).

The increase in travel associated with the rebound effect would produce additional benefits to vehicle owners and operators, which reflect the value of the increase in opportunities that would become accessible with additional travel. Given that vehicles are projected to make more frequent or longer trips when the cost of driving declines, the economic benefits from this supplementary travel are estimated to exceed supplementary expenditures for the fuel consumed.

The total travel benefits from increased distance travelled due to the rebound effect are estimated by adding the benefits realized from the additional fuel expenditures resulting from increased vehicle use, and the additional benefits (surplus) to vehicle owners and operators from increased distance travelled (“owner/operator surplus”). Owner/operator surplus was calculated by multiplying the estimated reduction in vehicle operating costs per kilometre by the projected increase in the annual number of kilometres driven. This result was then multiplied by one half, given that linear demand for vehicle-kilometres travelled was assumed. The value of benefits from increased vehicle use was estimated separately for each of the three main vehicle categories, as it depends on the extent of improvement in fuel efficiency.

| MYs 2018-2020 | MYs 2021-2023 | MYs 2024-2026 | MYs 2027-2029 | MYs 2018-2029 (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits related to refuelling time savings | |||||

| Tractor-trailers | 5 | 59 | 95 | 96 | 256 |

| Vocational vehicles | 0 | 14 | 26 | 41 | 82 |

| Heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans | 0 | 5 | 13 | 16 | 34 |

| Total | 5 | 79 | 134 | 154 | 372 |

| Travel benefits | |||||

| Tractor-trailers | 161 | 170 | 148 | 140 | 619 |

| Vocational vehicles | 0 | 191 | 170 | 162 | 522 |

| Heavy-duty pick-up trucks and vans | 0 | 123 | 105 | 95 | 324 |

| Total | 161 | 484 | 423 | 397 | 1,465 |

Note: Benefits are discounted to present value at 3% per year. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Calendar year analysis of benefits

From a calendar year point of view, from 2018 to 2050, the proposed standards could lead to a cumulative reduction of 137.4 Mt of CO2e emissions from all Phase 2 vehicles. In terms of fuel savings, these standards could lead to a cumulative reduction in fuel consumption from all Phase 2 vehicles of 52.2 billion litres from 2018 to 2050. Over this period, the total benefits for the calendar year analysis are projected to be $38.6 billion, mostly due to fuel savings ($30.0 billion), the value of increased travel opportunities ($3.4 billion) and the value of GHG emission reductions ($4.5 billion). The main results of the calendar year analysis of benefits are presented in Table 10.

| 2020 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 | 2018–2050 (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantified benefits | |||||

| GHG emission reductions (Mt of CO2e) | 0.02 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 8.2 | 137.4 |

| Fuel savings (millions of litres) | 9 | 1 167 | 2 368 | 3 109 | 52 199 |

| Monetized benefits (millions of dollars) | |||||

| Benefits due to GHG emission reductions | 1 | 115 | 204 | 231 | 4,482 |

| Benefits from fuel savings | 7 | 835 | 1,344 | 1,453 | 29,987 |

| Reduced refuelling time benefits | 0 | 21 | 34 | 34 | 744 |

| Travel benefits | 12 | 110 | 138 | 135 | 3,395 |

| Total | 20 | 1,081 | 1,720 | 1,852 | 38,609 |

Note: Fuel savings include reductions in both diesel and gasoline use and are monetized using pre-tax fuel prices. Benefits are discounted to present value at 3% per year. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Other impacts considered qualitatively

The proposed Amendments would lead to additional impacts other than those analyzed above. These additional impacts are expected to be small in magnitude relative to the main benefits and costs and would most likely only change the net benefit results by small amounts. These additional impacts have thus been considered qualitatively in this analysis and are discussed below.

Additional reductions in GHG emissions

The proposed Amendments would establish a leakage standard for refrigerants from air conditioning systems in vocational vehicles, which would serve to minimize leaks from these systems and thereby reduce emissions of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and other refrigerants. (see footnote 23) Although the impacts of reducing refrigerant emissions have not been quantified or monetized, these impacts are expected to add, to a small extent, to the overall benefits of GHG emission reductions estimated above.

Reductions in air pollutant emissions

The vehicles subject to the proposed Amendments are significant sources of air pollutants, such as fine particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulphur dioxide (SO2), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), carbon monoxide (CO) and other toxic substances. These pollutants affect ambient levels of secondarily formed PM2.5 and ozone. Exposure to ozone and PM2.5 (two principal sources of smog) is linked to adverse health impacts, including premature death, and chronic and short-term respiratory problems, as well as negative environmental effects on vegetation, buildings and visibility.

The vehicle, engine and trailer technologies that are expected to be adopted would lead to decreases in fuel consumption and hence reductions in emissions of smog-forming air pollutants, which would positively impact the health and environment of Canadians. In particular, auxiliary power units (APUs) are anticipated to be installed in transport tractors to provide power and climate control for drivers during extended idle operations. The operation of APUs as an alternative to main engine idling would lead to significant reductions in GHG emissions, as well as in emissions of NOx and VOCs. However, APUs powered by diesel would be sources of particulate matter emissions. To eliminate the unintended consequence of increased emissions of particulate matter from a more intensive use of APUs, the proposed Amendments would include a standard for these emissions from APUs installed in MY2021-2023 tractors, which would increase in stringency with MY2024 and later tractors.

Notwithstanding emissions of particulate matter from transport tractors equipped with diesel-powered APUs, the proposed Amendments would not directly regulate emissions of other air pollutants. Nevertheless, technologies that are anticipated to result in decreases in the fuel consumption of heavy-duty vehicles, such as decreases in total operating mass, aerodynamic drag and tire rolling resistance, as well as improvements in engine efficiency, would also lead to reductions in air pollutant emissions.

In order to assess the impacts of these anticipated changes, primary emissions of air pollutants were modelled for the BAU and regulatory scenarios in MOVES annually from 2018 to 2050 at the national level for NOx, SO2 and PM2.5. Due to the amount of time and modelling resources required to forecast VOC emissions from mobile sources, primary emissions of VOCs were modelled for the two scenarios in MOVES at the national level only for 2035.

Table 11 presents the changes in primary emissions of air pollutants from all Phase 2 vehicles in select years. Since the modelling of emissions was conducted early in the regulatory development process, prior to the proposal of standards for particulate matter emissions, the results below include projected increases in PM2.5 emissions, mainly due to increased APU use in tractors. It is expected that PM2.5 emissions would in fact decrease, given that the proposed Amendments incorporate standards for particulate matter emissions from APUs in alignment with the final U.S. Phase 2 rule.

| 2020 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in tonnes | ||||

| NOx | 23 | –3 570 | –7 090 | –9 859 |

| VOCs | — | — | — | –1 234 |

| PM2.5 | 1 | 33 | 64 | 89 |

| SO2 | 0 | –6 | –17 | –29 |

| CO | 6 | –1 007 | –1 971 | –2 701 |

| Change relative to the BAU scenario | ||||

| NOx | 0% | –3% | –6% | –9% |

| VOCs | — | — | — | –8% |

| PM2.5 | 0% | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| SO2 | 0% | –2% | –5% | –7% |

| CO | 0% | 0% | –1% | –1% |

Note: VOC emissions were modelled at the national level only for 2035 due to the amount of time and modelling resources required to model these emissions from mobile sources. Increases in PM2.5 emissions are shown here because the modelling was conducted prior to the inclusion of the standards for particulate matter emissions from APUs installed in tractors.

Health benefits

Prior to modelling emissions in MOVES and the introduction of the standards for particulate matter emissions from APUs in tractors, a scenario analysis was conducted by the Department of the Environment and the Department of Health to evaluate the potential magnitude of the health benefits of the changes in primary emissions of air pollutants expected to result from the proposed Phase 2 standards. Specifically, the relative (percentage) changes in emissions of key air pollutants from the analysis of the proposed U.S. Phase 2 rule were used as inputs and applied to the baseline emissions in 2035 from all on-road heavy-duty vehicles operating in Canada within A Unified Regional Air-Quality Modelling System (AURAMS). AURAMS was then used by the Department to estimate the impacts on ambient air quality resulting from the interaction of changes in vehicle emissions with existing ambient air quality, daily weather and wind patterns.

The Department of Health then applied the Air Quality Benefits Assessment Tool (AQBAT) to estimate the health and economic impacts associated with the air quality projections generated by AURAMS for 2035. In particular, the modelled changes in ambient air quality levels were allocated to each Canadian census division and used as inputs for AQBAT. Based on changes in local ambient air quality, AQBAT estimated the likely reductions in average per capita risks for a range of health impacts known to be associated with air pollution exposure. These changes in per capita health risks were then multiplied by the affected populations in order to estimate the reduction in the number of adverse health outcomes across the Canadian population. AQBAT also applied economic values drawn from the available literature to estimate the average per capita economic benefits of lowered health risks.

Based on this scenario, it was estimated that air quality improvements in 2035 would, at a minimum, generate health benefits valued at $60 million. This value is expected to be an underestimate of the health benefits resulting from the proposed Phase 2 standards, given that the air quality modelling was not updated to reflect the standards for particulate matter emissions from APUs in tractors. In addition, this value would likely represent the minimum annual health benefits for years after 2035, as an increasing portion of the on-road heavy-duty vehicle fleet would be subject to the proposed Phase 2 standards in these years as a result of fleet turnover.

The estimate of potential health benefits in this scenario analysis has not been included in the main results because detailed emission results from MOVES were not used as inputs within AURAMS, and the standards for particulate matter emissions in the proposed Amendments were not incorporated into the air quality modelling. By not including the potential health benefits in the net benefit calculations, the total monetized benefits have been underestimated.

Environmental benefits

Air pollutants such as NOx, VOCs, SO2 and PM2.5 are precursors to the formation of secondary particulate matter and ground-level ozone, which impact air quality and the environment by damaging forest ecosystems, crops and wildlife. The deposition of excess nitrogen on surface waters may also lead to lake and stream eutrophication, which poses a threat to aquatic life. Finally, smog and deposition of suspended particles may impair visibility and result in the soiling of surfaces, respectively, thereby reducing the welfare of residents and recreationists, and potentially increasing cleaning expenditures.

The environmental benefits associated with the proposed Amendments were not monetized, as precise modelling of the air quality impacts has not been undertaken. Nonetheless, the environmental benefits associated with the reductions in air pollutant emissions are expected to be positive.

Impacts of fuel savings on the upstream petroleum sector

Canada has a small, open economy and is a price-taker in the world petroleum market. Any impact on the prices of petroleum or refined petroleum products resulting from reductions in domestic fuel consumption due to the proposed Amendments is expected to be negligible. Any reduced domestic consumption from fuel savings is expected to be redirected from domestic consumption to increased exports or result in decreased imports, with minimal incremental impacts on the upstream petroleum sector in Canada.

Summary of benefits and costs: Model year analysis

The model year analysis considered the impacts attributable to MY2018-2029 vehicles (i.e. those vehicles produced within the time frame of the regulatory implementation), and the portion of their lifetime operation occurring from 2018 to 2050. From this point of view, the costs of the proposed Phase 2 standards are estimated at $4.8 billion, largely due to the additional costs of the vehicle technologies expected to be adopted to meet these standards. The total benefits for this model year analysis are projected to be $13.6 billion, mostly due to fuel savings ($10.3 billion), the value of increased travel opportunities ($1.5 billion) and the value of GHG emission reductions ($1.5 billion). Overall, the net benefits for MY2018-2029 vehicles are estimated at $8.8 billion. The results of this model year analysis are summarized in Table 12.

| MYs 2018-2020 | MYs 2021-2023 | MYs 2024-2026 | MYs 2027-2029 | MYs 2018-2029 (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monetized impacts (millions of dollars) Sectoral benefits |

|||||

| Pre-tax fuel savings | 107 | 1,996 | 3,714 | 4,493 | 10,311 |

| Refuelling time savings | 5 | 79 | 134 | 154 | 372 |

| Travel benefits | 161 | 484 | 423 | 397 | 1,465 |

| Societal benefits | |||||

| GHG emission reductions | 15 | 278 | 525 | 650 | 1,468 |

| Total benefits | 289 | 2,837 | 4,797 | 5,694 | 13,616 |

| Sectoral costs | |||||

| Vehicle technology costs | 98 | 1,011 | 1,351 | 1,682 | 4,142 |

| Tire maintenance costs | 25 | 43 | 45 | 44 | 156 |

| Business administrative costs | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Societal costs | |||||

| Accidents, congestion and noise | 53 | 182 | 162 | 153 | 550 |

| Government costs | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Total costs | 177 | 1,237 | 1,558 | 1,879 | 4,852 |

| Net benefits | 111 | 1,600 | 3,239 | 3,814 | 8,765 |

| Non-monetized impacts | |||||

| GHG emission reductions (Mt of CO2e) | 0.4 | 7.5 | 14.7 | 18.8 | 41.5 |

| Fuel savings (millions of litres) | 147 | 2 824 | 5 585 | 7 173 | 15 729 |

Impacts considered qualitatively

|

|||||

Note: Benefits and costs are discounted to present value at 3% per year. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

The time frame for assessing impacts in the model year analysis was 2018 to 2050. The emission reductions, fuel savings and related impacts resulting from MY2018-2029 Phase 2 vehicles during the portion of their lifetime operation that occurs after 2050 are not accounted for in the analysis. However, the magnitude of these impacts is anticipated to be relatively small, with benefits that outweigh the associated costs.

Summary of benefits and costs: Calendar year analysis

The calendar year analysis evaluated the annual impacts attributable to all Phase 2 vehicles from 2018 to 2050. The incremental costs of the technologies expected to be adopted over this time frame to meet the more stringent GHG emission standards are projected to be $13.9 billion. The total benefits are estimated at $38.6 billion, including fuel savings of $30.0 billion, GHG emission reductions valued at $4.5 billion and additional travel opportunities valued at $3.4 billion. Altogether, the net benefits for all heavy-duty vehicles are projected to be $23.2 billion. The annualized benefits, costs and net benefits are estimated to be $1.7 billion, $0.7 billion and $1.0 billion, respectively.

The time frame for the calendar year analysis was 2018 to 2050. Vehicle fleet turnover is expected to result in escalating GHG emission reductions and fuel savings over this period, as an increasing portion of the on-road fleet would meet more stringent emission standards. As a result of this turnover, the GHG emission reductions and fuel savings from Phase 2 vehicles are estimated to be considerably larger in 2050 than in 2030 (or earlier years), since a larger portion of the fleet would meet the Phase 2 standards in this later year. After 2050, as Phase 2 vehicles continue to replace pre-Phase 2 vehicles, benefits that outweigh the associated costs are expected over the lifetime of these new Phase 2 vehicles. In addition, the emission reductions and related benefits resulting from MY2018-2050 Phase 2 vehicles during the portion of their lifetime operation that occurs after 2050 are not accounted for in the analysis.

By 2030, the proposed Phase 2 standards are estimated to achieve cumulative reductions of CO2e emissions of 14.5 Mt. To attain these GHG emission reductions over the 2018–2030 period, industry stakeholders would carry sectoral costs of around $4.8 billion and realize sectoral benefits of about $5.0 billion. Overall, the anticipated reductions in GHG emissions over this period would be achieved at a sectoral (industry) cost per tonne of $329, and at an industry cost per tonne that takes sectoral benefits into account (i.e. a net industry cost per tonne) of –$16. However, the vast majority of the emission reductions from Phase 2 vehicles would take place after 2030, given that over 80% of the total distance travelled by these vehicles, from 2018 to 2050, is expected to occur after 2030. Over the 2018–2050 period, industry stakeholders would carry sectoral costs of about $14.2 billion and realize sectoral benefits of around $34.1 billion. The projected reductions in CO2e emissions of 137.4 Mt would be achieved over this period at an industry cost per tonne of $103, and at a net industry cost per tonne of –$145.

| Type of Cost per Tonne | Sectoral Costs (millions) | GHG Emission Reductions (Mt of CO2e) | Cost per Tonne of GHG Emissions Reduced |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018–2030 | |||

| Industry cost per tonne | $4,770 | 14.5 | $329 |

| Net industry cost per tonne | –$230 | 14.5 | –$16 |

| 2018–2050 (total) | |||

| Industry cost per tonne | $14,213 | 137.4 | $103 |

| Net industry cost per tonne | –$19,913 | 137.4 | –$145 |

Note: Net industry costs are calculated by subtracting sectoral benefits from sectoral costs associated with all Phase 2 vehicles for the specified period. Benefits and costs are discounted to present value at 3% per year.

These cost-per-tonne results, as shown in Table 13, do not account for the value that society places on avoided climate change impacts or the timing of the emissions within the specified period.

Sensitivity analysis

The results of this analysis are based on key parameter estimates, which could be higher or lower than indicated by available evidence. Given this uncertainty, alternative impact estimates have been considered to assess their effects on the expected net benefit results. In particular, a worst-case scenario of both higher costs and lower benefits was considered. As shown in Table 14, there are expected net benefits using discount rates of 3% and 7%, and over a range of alternative impact estimates, which is evidence that the net benefit results are likely robust.

| Alternatives (model year analysis) | Benefits (B) | Costs (C) | Net Benefits (B–C) | Benefit-cost Ratio (B/C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95th percentile values for the GHG social costs | 18,476 | 4,850 | 13,626 | 3.8 |

| Central case (from Table 12) | 13,616 | 4,850 | 8,767 | 2.8 |

| Impacts discounted at 7% per year | 7,314 | 3,321 | 3,993 | 2.2 |

| Costs 40% higher than estimated | 13,616 | 6,790 | 6,827 | 2.0 |

| Benefits 40% lower than estimated | 8,170 | 4,850 | 3,320 | 1.7 |

| Costs 40% higher and benefits 40% lower | 8,170 | 6,790 | 1,380 | 1.2 |

Note: Benefits and costs are discounted to present value at 3% per year, except in the cases in which a 7% rate is used. Totals may not sum due to rounding.