Canada Gazette, Part I, Volume 156, Number 53: Regulations Amending the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations

December 31, 2022

Statutory authority

Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999

Sponsoring departments

Department of the Environment

Department of Health

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: As noted in the 2022 Emission Reduction Plan, there is an urgent need to address climate change and move towards a low-carbon economy. Greenhouse gases (GHGs) are primary contributors to climate change and the transportation sector accounts for 25% of domestic greenhouse gas emissions in Canada. Passenger car and light trucks account for about half of the transportation sector’s emissions. Decreasing emissions in all sectors, including transportation, is necessary to tackle climate change and reach the Government’s emission reduction target of 40 to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030 and net zero by 2050.

Description: The proposed Regulations Amending the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations (hereinafter referred to as the proposed Amendments) would introduce new requirements for manufacturers and importers to ensure that their fleet of new light-duty vehicles offered for sale in Canada meets specified annual targets of zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs). These ZEV sales targets would begin with model year 2026 and reach full stringency in 2035. In addition, the proposed Amendments would modify flexibilities and fix provisions related to the pre-2026 model year fleet average GHG emission standards.

Rationale: In March 2022, the Government published Canada’s 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan (PDF) [ERP], providing a roadmap to reach its climate commitments, such as reducing national GHG emissions by 40 to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030 under the Paris Agreement, and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. The ERP included a plan to introduce a regulated ZEV sales target that will require 100% of passenger car and light truck sales be zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) by 2035, with interim targets of at least 20% by 2026, and at least 60% by 2030.

Cost-benefit statement: From 2026 to 2050, the proposed Amendments are estimated to have incremental ZEV vehicle and home charger costs of $24.5 billion, while saving $33.9 billion in net energy costs. These impacts accrue to those who switch to ZEVs in response to the proposed Amendments. The cumulative GHG emission reductions are estimated to be 430 megatons (Mt), valued at $19.2 billion in avoided global damages. The proposed Amendments are thus estimated to have net benefits of $28.6 billion and would help Canada meet its GHG emissions reduction targets of 40% below 2005 levels by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2050.

Issues

As noted in the 2022 Emission Reduction Plan,footnote 2 there is an urgent need to address climate change and move towards a low-carbon economy. Greenhouse gases (GHGs) are primary contributors to climate change and the transportation sector accounts for 25% of domestic greenhouse gas emissions in Canada. Passenger car and light trucks account for about half of the transportation sector’s emissions. Decreasing emissions in all sectors, including transportation, is necessary to tackle climate change and reach the Government’s GHG emissions reduction target of 40 to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030 and net zero by 2050.

Additionally, the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations (PALTGGER or the Regulations) require changes to administrative provisions and flexibilities for pre-2026 model years, based on a 2021 departmental review of the Regulations.

Background

The Regulations were published in October 2010 under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA), establishing GHG emission standards for light-duty vehicles (LDVs) of the 2011 to 2016 model years, in alignment with new United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standards. These regulations required importers and manufacturers of new vehicles to meet increasingly stringent fleet average GHG emission standards. In 2014, Canada amended the Regulations to establish GHG emission standards for the 2017 to 2025 model years, in alignment with revised U.S. EPA standards. These Regulations also adopted an incorporation by reference approach to minimize regulatory burden with continuously evolving U.S. EPA regulations.

In 2018, the United States completed a mid-term evaluation of its amended regulations, determining that the standards in later years were too stringent and ought to be reduced. In 2020, a U.S. Final Rule was published to reduce the stringency of the fleet average GHG emission standards for model years 2021 through 2026 from approximately 5% per year to approximately 1.5%. Canadian standards consequently became less stringent given the U.S. GHG emission standards were incorporated by reference into the Regulations. In February 2021, Canada completed its own effortsfootnote 3 to assess the impact of the recent U.S. Final Rule and the feasibility of establishing more stringent fleet average GHG emission standards in Canada relative to those in the U.S. Final Rule. However, the U.S. EPA released a new Final Rule later that year, increasing the stringency by about 10% for model years 2023 and 2026 and by at least 5% for model years 2024–2025. Prior to the publication of the EPA Final Rule, Canada announced through the Strengthened Climate Plan, that it would work to align the Regulations with the most stringent GHG emission standards in North America post-2025, whether at the United States federal or state level. The U.S. EPA also announced its intention to publish strengthened passenger automobile and light truck (hereinafter referred to as light-duty vehicle [LDV]) GHG emission standards, and is expected to publish a Notice of Proposed Rule Making for post-2026 emission standards in March 2023.

In June 2021, the Government approved a renewed and integrated zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) strategy for LDVs, setting a mandatory target for 100% of new LDV sales to be zero emission by 2035.footnote 4 The policy marked the transition to a more independent regulatory policy in the transportation sector in recognition of Canada’s ambition to tackle climate change. In March 2022, the Government published Canada’s 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan (PDF) [ERP], providing a roadmap to reach its climate commitments, such as reducing national GHG emissions by 40 to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030 under the Paris Agreement, and achieving net-zero GHG emissions by 2050. The ERP included a plan to introduce regulations requiring that 100% of passenger car and light truck sales be zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) by 2035, with interim targets of 20% by 2026 and 60% by 2030.

Complimentary measures led by other federal departments

Throughout the development of proposed amendments to the Regulations [hereinafter referred to as the proposed Amendments], there were extensive consultations and coordination with other government departments, and in particular with Transport Canada (TC), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), and Innovation, Science, and Economic Development Canada (ISED). Each of these departments is responsible for implementing key complementary measures that will help to support Canada’s transition from GHG emitting vehicles to ZEVs.

ZEV infrastructure

Since 2016, the Government of Canada has made significant investments in zero-emission vehicle infrastructure including through NRCan’s Electric Vehicle and Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Deployment Initiative and the Zero Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Programfootnote 5 (ZEVIP). Budget 2019 provided NRCan with $130M over five years to implement ZEVIP. Furthermore, the 2020 Fall Economic Statement provided an additional $150M to further expand Canada’s zero-emission vehicle infrastructure and deploy a total of 33 500 new recharging stations and 10 hydrogen refuelling stations in targeted areas. Some of these targeted areas include multi-unit residential buildings, workplaces, commercial spaces, street charging and public parking spots, and remote areas.

ZEVIP follows NRCan’s Electric Vehicle and Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Deployment Initiative,footnote 6 which ended on March 31, 2022. This initiative supported the deployment of fast chargers for electric vehicles coast-to-coast along Canada’s highway system, natural gas stations along key freight routes, and hydrogen refuelling in key metropolitan areas. As of October 2022, these two programs have approved projects across 12 provinces and territories, which will result in 34 887 new chargers, 22 natural gas stations and 33 hydrogen stations. Budget 2022 included an additional $400M to recapitalize ZEVIP, and $500M to Canada’s Infrastructure Bank (CIB) to invest in large-scale ZEV charging and refuelling infrastructure that is revenue generating and in the public interest.

ZEV incentives

In May of 2019, the Government of Canada launched the Incentives for Zero-Emission Vehicles (iZEV) Program.footnote 7 This TC-led program provides purchase incentives of up to $5,000 for eligible light-duty vehicles. Since May 2019, over 175 000 incentives have been provided to Canadians and Canadian businesses. The iZEV Program was expanded in April 2022 to capture larger ZEV models, and currently there are over 35 eligible models available for sale in Canada. Budget 2022 provided $1.7B for this initiative, enabling iZEV to be in place until the $1.7B is spent, or by latest, March 31, 2025.

ZEV industrial transition

Via ISED’s Strategic Innovation Fund (SIF),footnote 8 the Government is supporting industry efforts to accelerate the production of low and zero-emission vehicles and the battery supply chain. Since 2018, investments of nearly $16 billion in Canada from cathode active battery materials (CAM), their precursor materials (pCAM), electric vehicle (EV) assembly and battery cell manufacturing have been announced.footnote 1

Objective

The objectives of the proposed Amendments are to further reduce GHG emissions in the transportation sector, as laid out in the Government of Canada’s commitment in the ERP and to fix errors in the current text of the Regulations. In addition, the proposed Amendments aim to reduce the regulatory burden for companies operating in both the Canadian and U.S. markets, by ensuring the administrative requirements for GHG vehicle emission standards are aligned between the two jurisdictions.

Description

The Regulationsfootnote 9 were adopted in 2010 for the purpose of reducing greenhouse gas emissions from passenger automobiles and light trucks by establishing fleet average GHG emission standards and test procedures that are aligned with the federal requirements of the United States. The proposed Amendments would introduce new requirements establishing ZEV sales targets, beginning with model year 2026, as well as make administrative amendments to the current Regulations on pre-2026 model year vehicles, beginning with model year 2023.

Zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) sales targets

The proposed Amendments would be made under CEPA, and would establish annual ZEV sales targets and a compliance credit system. The proposed Amendments would require manufacturers and importers to meet an annual percent target of new light-duty ZEVs offered for sale in Canada (hereinafter referred to as ZEV sales targets). These annual ZEV sales targets are as follows:

| Model Year | ZEV sales targets (%) |

|---|---|

| 2026 | 20 |

| 2027 | 23 |

| 2028 | 34 |

| 2029 | 43 |

| 2030 | 60 |

| 2031 | 74 |

| 2032 | 83 |

| 2033 | 94 |

| 2034 | 97 |

| 2035 and beyond | 100 |

The proposed Amendments would establish a methodology for determining whether the fleet offered for sale in Canada meets the ZEV sales target for a given model year. If a company exceeds its ZEV sales target, it earns compliance units (hereinafter referred to as credits) for excess ZEV units offered for sale. If a company misses its ZEV sales target, it incurs a compliance deficit, which must be satisfied by obtaining credits. Compliance deficits can be satisfied with banked credits (see below), by purchasing credits from other companies, or by creating credits from contributing to designated ZEV activities (see further below).

The proposed Amendments would allow a company to bank excess credits in any given model year to use towards compliance for up to five model years after the model year in which the credits were created. Companies would not be permitted to use excess credits to meet their sales targets starting in model year 2035 and beyond. In addition, deficits incurred in model years 2026 to 2034 would be required to be offset no later than the third model year after the one in which the company incurred the deficit and no later than model year 2035.

The value of a credit would be based on the type of ZEV and the model year. A battery electric vehicle (BEV), fuel cell vehicle (FCV), or plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV) with an all-electric range of more than 80 km would receive one credit and PHEVs with an all-electric range of less than 80 km would receive a portion of a credit.

More specifically, a PHEV with an all-electric range of 16 to 49 km would receive 0.15 credits and would qualify to earn credits only in model year 2026. A PHEV with an all-electric range of 50 to 79 km would receive 0.75 credits and would qualify to earn credits up to model year 2028. In addition, notwithstanding its all-electric range, the proposed Amendments would limit the contribution of PHEVs towards the ZEV sales target to 45% for model year 2026, 30% for model year 2027 and 20% for model years 2028 and beyond.

The proposed Amendments would also introduce a flexibility mechanism that would allow regulated entities in a deficit situation to create credits through contributing to specified ZEV activities, such as supporting charging infrastructure growth to meet their obligation. The number of credits that a company can create through a contribution for a given model year will also be capped. The cap will begin at 2% of a company’s fleet of new vehicles in model year 2026 and the cap will gradually increase annually to reach 6% by model year 2030. The cap of the company’s fleet of new vehicles for model years 2031 to 2034 will remain at 6% and this option will no longer be available thereafter. Regulated companies would earn one compliance credit for each contribution of $20,000 (indexed annually to the Consumer Price Index).

Administrative amendments to the Regulations

The proposed Amendments would amend several housekeeping amendments to the pre-2026 model year administrative requirements. These amendments would implement changes identified in Canada’s mid-term evaluation of the Regulations in order to align with some of the changes in the U.S. EPA 2020 and 2021 Final Rules. In addition, they would make other corrections, clarify provisions and update references in the current version of the Regulations.

Regulatory development

Consultation

Environment and Climate Change Canada (the Department) has consulted with non-governmental organizations (NGO), industry associations, manufacturers, academics, other government departments, provincial/ territorial/municipal governments, and the public. Starting in August 2020, the Department began to engage the stakeholder community as part of the mid-term review of the PALTGGER. This involved a series of webinars and online consultation sessions in the summer and fall, following the publication of a Final Rule by the U.S. EPA in April 2020. Another webinar session was held in February 2021 following the publication of a revised U.S. final decision document on the mid-term evaluation.

In December 2021, the Department released a discussion paper,footnote 10 which sought input on measures needed to achieve Canada’s 2035 zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) sales targets for all new light-duty vehicles. Stakeholders were invited to provide written feedback until January 21, 2022. In August 2022, a Light-Duty Vehicle Technical Working Group (“Technical Working Group”) was established to share technical information and views on regulations to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from LDVs in Canada and transition toward zero-emission vehicles. In addition to these meetings, departmental officials have held over 30 bilateral meetings with stakeholders and partners.

Industry comments

The automotive industry prefers that Canada continues to align with U.S. EPA fleet average GHG emission standards regulations, stating that the emission standards are the most effective way to meet the GHG and ZEV targets while protecting industry competitiveness in an integrated North American auto market. Automakers noted that they were all investing in ZEVs and that ZEVs would be the primary technology used to comply with future performance-based GHG standards in the United States, noting the European Union (EU) also aims to reach 100% ZEV sales via performance standards.

The Department agrees with the need to maintain alignment with the U.S. EPA fleet average GHG emission standards to continue reducing GHG emissions from new vehicles offered for sale in Canada, in order to minimize the overall regulatory burden for companies operating in the Canada–U.S. market and maintain fair regulatory conditions for importers and manufacturers. Therefore, the proposed Amendments include provisions to maintain alignment with some changes in the U.S. EPA Final Rule published in December 2021 for model years 2023 to 2026.

The Department also committed to align Canada’s LDV regulations with the most stringent performance standards in North America post-2025, whether at the United States federal or state level.footnote 11 In August 2021, the U.S. EPA was directed by Executive Order to establish new multi-pollutant emissions standards, including for greenhouse gas emissions, for light- and medium-duty vehicles beginning with model year 2027 and extending through and including at least model year 2030. The Department understands that, at this time, these upcoming new standards, which are expected to be proposed in 2023, will be the most stringent in North America, and expects to align with them.

With the exception of companies who exclusively manufacture electric vehicles, vehicle manufacturers and their representing associations were strongly against the development of a national ZEV sales mandate. The associations for automakers have also expressed concerns with timelines. Some automotive firms have shared product plans of fleet composition to demonstrate they would not be in a position to comply with the proposed ZEV requirements.

The Department has considered various approaches to decarbonize the transportation sector and determined that the use of both GHG emission performance standards and ZEV requirements will work in tandem towards achieving Canada’s emission reduction targets. This approach would ensure that the internal combustion fleet continues to improve its efficiency and reduce its per unit emissions on the way to a zero-emission future. In response to concerns regarding the feasibility of meeting compliance obligations, the Department has designed the annual targets to reflect a slower increase in stringency in early years to give manufacturers and importers time to adapt. In addition, a compliance flexibility mechanism would be introduced whereby regulated entities may purchase credits from other manufacturers and importers, or may create credits by contributing to ZEV activities.

These vehicle manufacturers and their associations advocated for strong demand-sided policies, including increased consumer rebates to support the purchase of ZEVs, accelerated deployment of existing resources for charging infrastructure, worker upskilling and consumer education programs, to supplement the supply-sided policies that are being implemented. These concerns were also raised by NGOs as well as provinces and territories in their comments. Vehicle manufacturers went a bit further by asking that the proper infrastructure be in place before introducing a ZEV mandate.

Vehicle manufacturers and their associations have also called on the Government of Canada to match the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act’s new Advanced Manufacturing Production Tax Credit, which will offer per-vehicle subsidies for EV manufacturing in the United States.

The Department notes that the proposed Amendments are part of a suite of federal commitments that aim to reach Canada’s 2030 emission reduction targets and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. In particular, they are supported through financial incentives for ZEVs, led by Transport Canada, and significant investments in charging and refuelling infrastructure, administered by Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) and the Canada Infrastructure Bank. NRCan continues to work on various awareness activities, such as the Zero Emission Vehicle Awareness Initiative, initiated in 2019, to support education and awareness projects across all vehicle classes. To address worker upskilling concerns, ISED has supported industry efforts to accelerate the production of ZEVs and the battery supply chain through investments that have been retaining and creating jobs and opportunities for workers and their communities. For more information on these different programs, refer to the “Background” section, under “Complimentary measures led by other federal departments.”

Some companies mentioned the increased administrative reporting burden associated with ZEV sales targets. The Department notes that manufacturers and importers are already required to submit compliance reports under PALTGGER. The new ZEV provisions would generate slight additional reporting requirements in existing annual compliance reports by requiring documentation on credit acquisition. For more information on administrative costs from the additional reporting requirements, refer to the “Background” section under “Complimentary measures led by other federal departments.”

Non-governmental organization comments

The vast majority of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) strongly advocated for a ZEV sales target to accelerate GHG reductions and to make Canada less dependent on changes in U.S. regulatory ambitions. They shared that a ZEV mandate would provide a solid signal to all industries and would allow Canada to achieve its GHG objectives in the transportation sector. Stakeholders also expressed general agreement that annual stringencies should be part of the design to monitor progress towards the target and to enable the Government to correct course as 2035 draws nearer. The proposed Amendments set annual increasing ZEV sales targets to ramp up to 100% by 2035 (see the “Description” section above). Compliance would be reviewed annually through existing annual compliance reports, which would now also require documentation on credit acquisition.

Generally, NGOs were divided regarding the inclusion of PHEVs in the definition of ZEVs; however, all agreed that if PHEVs are to be included, they should be treated as a temporary transitionary technology, and vehicles should possess a minimum all-electric range as well as receive only partial zero-emission recognition, such as in the case of compliance credits. The Department did not change the definition of an advanced technology vehicle, which continues to include PHEVs, since PHEVs will be an important technology in northern and remote communities. However, the proposed Amendments limit the quantity and credit value of PHEV credits. It is therefore expected that PHEVs would constitute only a small portion of new ZEVs by the end of the decade as they bridge the gap between conventional and battery electric vehicles.

Comments from provinces and territories:

Representatives from most provinces participated in consultations. Provinces generally expressed support for a national ZEV mandate with annual targets, and provinces with mandates shared their experience to date in regulatory development and implementation, while providing insight into future regulatory plans.

The affordability of ZEVs is a main concern, and some provinces were curious to know when cost parity would occur. They stressed that the policy should consider the needs of rural residents and low-income groups. Provinces noted that PHEVs would help to address remote and rural concerns, which include a lack of infrastructure, the impact on infrastructure and safety, due to the additional weight of ZEVs, and price increases due to the shortage of, and high demand for, vehicles. The proposed Amendments would permit the use of PHEVs to meet credit obligations while addressing the needs of remote, northern and rural communities. For cost information, refer to the “Regulatory analysis” section, under “Monetized (and quantified) impacts.”

The proposed Amendments do not include regional ZEV requirements, although some provinces have raised concerns about ZEVs being more concentrated in provinces with mandates. After a careful review, the Department decided not to include regional requirements, as there is no practical way to establish regional sales mandates at the federal level. Moreover, ZEVs continue to gain market share throughout the country, and national requirements would give automakers the flexibility to respond to markets with high consumer interest and infrastructure readiness. Manufacturers and importers indicated that ZEV supply for a manufacturer is allocated on a national basis, and that regional requirements would not generate any additional supply for Canada.

Departmental consideration of ZEV requirements for northern or remote communities

The proposed Amendments do not provide exemptions for northern or remote communities. However, the Department recognizes that the transition to ZEVs will be challenging for northern and remote communities and is continuing to evaluate measures that could help facilitate this transition.

Modern treaty obligations and Indigenous engagement and consultation

As required by the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation, an assessment of modern treaty implications was conducted on the proposal. The assessment examined the geographic scope and subject matter of the proposed Amendments in relation to modern treaties in effect. The assessment did not identify any modern treaty implications or obligations.

Instrument choice

The objective of the proposed Amendments is to reduce emissions from passenger vehicles to achieve announced climate targets. Maintaining the status quo would likely not go far enough to achieve Canada’s emission reduction target of 40 to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030. In addition, the historical method of reducing emissions from passenger automobiles and light trucks through the use of increasingly stringent fleet average GHG emission standards alone may not achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. Even with carbon pricing increasing the operating cost of a non-ZEV vehicle, the high upfront cost of ZEVs, vehicle all-electric driving range anxiety, and status quo bias may not lead to the necessary level of ZEV adoption to meet Canada’s climate targets. The Department therefore determined that the only viable option to achieve the stated objective was to transition the fleet of light-duty vehicles to zero-emission alternatives through the use of increasing ZEV sales targets.

Regulatory analysis

The proposed Amendments making administrative changes to the Regulations are not expected to have a measurable impact, as they are largely technical in nature. Therefore, impacts estimated in this analysis are attributable only to the proposed Amendments to introduce ZEV sales targets.

From 2026 to 2050, the proposed ZEV Amendments are estimated to have incremental ZEV and home charger costs of $24.5 billion, while saving $33.9 billion in net energy costs. The cumulative GHG emission reductions are estimated to be 430 Mt of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e), valued at $19.2 billion in avoided global damages. The estimated net benefits of the proposed Amendments are $28.6 billion in this analysis.

Analytical framework

To estimate the impact of the proposed Amendments, a cost-benefit analysis was conducted to account for three main categories of monetized impacts, similar to the approach taken for the mid-term review of the Regulations.footnote 3 These impacts are incremental ZEV and home charger costs, net energy savings, and GHG emission reductions. The time frame for analysis is 25 years (2026 to 2050), which covers the period when the proposed ZEV requirements come into effect (model year 2026) and then reach full stringency (model year 2035) and extends to 2050 to illustrate the trend in cumulative net benefits resulting from the ongoing shift to more ZEVs in the light-duty vehicle fleet in response to the proposed Amendments.

ZEV costs are estimated from published sources such as Statistics Canada and the California Air Resources Board (CARB), while net energy savings and GHG emission reductions are estimated using the output from the Department’s Energy, Emissions, and Economy Model for Canada (E3MC). The value of GHG emission reductions is calculated using the Department’s social cost of carbon (SCC) method. Air pollution reductions are also quantified but not monetized, while other impacts are considered qualitatively. The incremental impacts are derived by comparing a baseline scenario to a regulatory scenario that reflect key aspects of the proposed ZEV Amendments. Where sources used USD, dollars were converted to CAD using 2021 purchasing power parity.footnote 12 All dollar figures are presented in 2021 Canadian prices and discounted at 3% annually (to 2023) when presented in present value form.

Baseline scenario

The baseline scenario is based on projections from the 2021 Departmental Reference Case.footnote 13 These projections take into consideration current policies in place such as the zero-emission vehicle regulations in Quebec and British Columbia. In addition, since Canadian passenger car and light truck fleet average GHG emission standards are incorporated by reference with the United States, the baseline scenario takes into account the regulated fleet average fuel efficiency standards up to model year 2026, as set out in the EPA’s Final Rule to revise GHG emissions standards for LDVs published in 2021.footnote 14 Beyond 2026, fleet average GHG emission standards are assumed to remain constant at the 2026 level. As such, the baseline scenario approximates future GHG emissions and energy consumption based on current practices and implemented policy measures. Thus, this analysis does not account for future policies, such as the more stringent post-2026 GHG standards that are expected to be published by the EPA in 2023, which would subsequently be adopted in Canada through incorporation by reference under the Regulations.

The number of new vehicles sold each year is derived using 2019 new vehicle sales data from Statistics Canada.footnote 15 In 2019, total new vehicle sales were 1.98 million. Starting in 2022, this analysis assumes that new vehicle sales will grow at the rate of population growthfootnote 13 in Canada. The years 2020 and 2021 were omitted due to the special economic circumstances of COVID-19 that impacted the industry. Transport Canada’s 2021 projections on ZEV-penetration rates, which are incorporated in the 2021 Departmental Reference Case, are then applied to estimate the share of ZEV vehicle sales in the baseline scenario. Furthermore, Transport Canada projections on the relative percent of each type of ZEV are also applied to estimate the number of new sales for the four representative ZEV types included in this analysis.

Regulatory scenario

The regulatory scenario is based on the assumption that the proposed Amendments achieve the specified year-by-year ZEV sales targets. ZEV sales targets are specified by model year, and the analysis assumes that each model year results occur in the same calendar year. E3MC was then used to model how an increase in the percentage of ZEVs impacts GHG tailpipe emissions and vehicle energy use. Fleet average GHG emission standards for non-ZEVs are held constant in the regulatory scenario. Costs are based on estimated incremental ZEV prices and increased share of ZEVs (with home chargers).

The proposed Amendments would establish a minimum number of credits required for a regulated company to meet compliance. The year-by-year stringency of the ZEV sales targets would begin with model year 2026 and reach 100% by model year 2035. The value of the ZEV credits would be based on the type of ZEVs in each firm’s overall fleet, but the analysis does not consider how the types of credits earned by firms might affect the type of ZEVs manufactured or imported. Options for credit banking are also offered in the proposed Amendments, but the analysis assumes there is no credit banking.

The proposed Amendments would also offer industry a compliance flexibility option through which manufacturers or importers could purchase credits by contributing to ZEV activities to meet a portion of their annual obligation between 2026 and 2034. After 2034, this compliance flexibility would no longer be available. Given that the proposed price of this credit (indexed to 2026 at a cost of $20,000) is much higher than the estimated incremental costs of ZEVs, the analysis assumes that vehicle manufacturers and importers would not typically choose to invest in the fund, but instead could generally meet 100% of their annual compliance obligation through the manufacture or importation of additional ZEVs.

Figure 1: Projected annual share of ZEV sales in the baseline and regulatory scenarios

Figure 1: Projected annual share of ZEV sales in the baseline and regulatory scenarios - Text version

Figure 1 is a line graph that illustrates annual ZEV sales as a share of overall light-duty vehicle sales in the baseline and regulatory scenarios. The y-axis represents ZEV sales as a percentage of overall light-duty vehicle sales, ranging from 0 to 100%. The x-axis represents the years, ranging from 2026 to 2050. There are two lines on this graph. The first line, the dotted line, illustrates the expected trajectory of the share of ZEVs in the baseline scenario. This line begins at just under 20% and has a positive slope through to 2050 where it ends at roughly 80%. The second line, the solid line, represents the trajectory of the share of ZEVs in the regulatory scenario, and follows the annual stringencies as set out in Table 1. This line begins at 20% in 2026, and increases more rapidly than the baseline scenario, reaching 100% in 2035 where it flattens through to 2050.

Monetized (and quantified) impacts

The analysis estimates the incremental costs of more ZEVs, home chargers and ZEV administrative requirements, as well as the benefits of net energy savings from switching to ZEVs. GHG emission reductions are quantified and monetized, while air pollution reductions are only quantified in this analysis.

Costs of manufacturing ZEVs and home chargers, and administrative reporting requirements

The proposed Amendments are expected to result in incremental vehicle and home charging costs for manufacturing (or importing) more ZEVs in response to the proposed Amendments. In this analysis, the total number of new vehicles is assumed to be the same in both the baseline and regulatory scenarios. To project the number of vehicle sales out to 2050, Statistics Canada vehicle sales data from 2019 is grown using a 1% projected population growth rate from the 2021 Departmental Reference Case. In the regulatory scenario, the share of new ZEVs is increased to align with the annual ZEV targets. The analysis estimates costs to switch to four types of ZEVs: medium-sized BEV cars, BEV pickup trucks each with a 480 km all-electric range, medium-sized PHEV cars and PHEV pickup trucks with an 80 km all-electric range. In 2035, medium-sized BEVs account for 30% of ZEV sales, BEV pickup trucks are roughly 50%, and PHEVs make up the remaining 20% of sales. The proportion of each type of vehicle as a share of overall ZEV sales remains constant in the two scenarios.

Manufacturing costs for ZEVs tend to be higher than those for non-ZEVs and are expected to be passed directly to consumers who switch to ZEV purchases in the regulatory scenario, although price differences are expected to decrease over time. Estimated incremental vehicle costs for this analysis are adopted from a California Air Resources Board (CARB) reportfootnote 16 with prices (excluding subsidies) expressed as 2020 USD (but reported here in 2021 CAD). All ZEVs are assumed to have the additional cold-weather and all-wheel drive (AWD) features. The report estimates that the medium-sized BEV would have an incremental cost of $3,300 in 2026 and would decrease in price, becoming less expensive than its non-ZEV equivalent by 2033. The three other vehicle types do not reach price parity with non-ZEVs. Battery-electric pickup trucks in this report cost an additional $7,150 in 2026, which decreases to an estimated incremental cost of $655 by 2035. Medium-sized PHEV cars are estimated to cost an incremental $3,950 in 2026 and $2,550 by 2035. PHEV pickup trucks are estimated to cost an incremental $5,700 in 2026 and $3,600 by 2035. After 2035, the analysis holds these incremental prices constant. The total incremental cost of purchasing more ZEVs is estimated to be $15.3 billon in present value terms.

| Type of zero-emission vehicles | 2026 | 2030 | 2035 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Battery electric cars | 3,300 | 985 | (795) |

| Battery electric light trucks | 7,150 | 3,450 | 655 |

| Plug-in hybrid electric cars | 3,950 | 3,175 | 2,550 |

| Plug-in hybrid electric trucks | 5,700 | 4,500 | 3,600 |

In addition to purchasing the vehicle itself, many consumers would purchase charging equipment for at-home vehicle charging. Electric vehicles can charge directly with a 120-volt plug; however, a level two alternating current (AC) charger requires a 240-volt plug and would increase the speed of charging from a range of 4–6 km per hour spent charging to 16–32 km per hour spent charging. According to a report by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS),footnote 17roughly 80% of electric vehicles (EVs) are bought with a level two residential charger, at a cost of roughly $480 to $870 in 2021 CAD. The higher cost was employed — this may overestimate the cost of charging equipment; however, installation costs have not been accounted for in this analysis and thus may be underestimated. In addition, the analysis may overestimate charger costs as the quantity of home chargers per quantity of vehicles sold is held constant throughout the time frame of the analysis; however, it is expected that the share of vehicles purchased with a charger will decrease over time as consumers begin replacing existing ZEVs as opposed to non-ZEVs. The cost to consumers to purchase charging equipment is determined by multiplying the estimated per-unit cost by 80% of the incremental number of ZEVs sold for a total cost of $9.1 billion in present value terms. Alternative scenarios are tested in the sensitivity analysis.

The total incremental costs to purchase ZEVs and home chargers are estimated at $24.5 billion in present value terms, as shown below.

The annual incremental costs to purchase more ZEVs and chargers increase with the stringency of the proposed Amendments from 2026 to 2035, and then fall in subsequent years as the number of baseline ZEVs increase annually, as shown below.

Figure 2: Annual ZEV and home charger costs

Figure 2: Annual ZEV and home charger costs - Text version

Figure 2 illustrates a bar graph, with the y-axis representing the estimated cost of ZEVs and their chargers in millions of dollars, and the x-axis representing the years from 2026 to 2050. Costs in 2026 and 2027 are just under $500 million, jumping to almost $1.5 billion in 2028, and continuing its upward trajectory until it peaks in 2031 at roughly $3 billion. After this point, costs continually decrease year over year until 2050 where they end at roughly $750 million.

Manufacturers and importers are already required to submit compliance reports to the Department under the PALTGGER. However, the proposed Amendments would require the inclusion of additional information. The proposed Amendments introduce a new credit system where manufacturers and importers would be required to submit documentation on credit acquisition — through the production or importation of ZEVs, investments in projects that support ZEV use, or the trade of credits with other manufacturers or importers. Administrative costs from the additional reporting requirements are estimated to be $74,000 annually, with an additional $4,000 in upfront costs associated with learning about the proposed Amendments in the first year. Over the time frame of analysis, these administration costs are estimated to be $1.2 million in present value terms.

Compliance costs to manufacture or import more ZEVs and chargers, and meet the administrative requirements of the proposed Amendments, are $24.4 billion, as shown below.

Table 3: Summary of monetized costs (millions of dollars)

- Number of years: 25 (2026 to 2050)

- Dollar year for prices: 2021

- Present value year for discounting: 2023

- Social discount rate: 3% per year

| Monetized benefits (costs) | Undiscounted — 2026 | Undiscounted — 2035 | Undiscounted — 2050 | Discounted — 2026 to 2050 | Annualized |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle costs | 353 | 798 | 321 | 15 316 | 880 |

| Charger costs | 43 | 812 | 373 | 9 129 | 524 |

| Administrative costs | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 1.2 | 0.07 |

| Total ZEV costs | 396 | 1 611 | 694 | 24 446 | 1 404 |

It is expected that these incremental costs would be passed onto ZEV purchasers. These consumers are also expected to incur ongoing costs associated with charging their ZEVs instead of paying fossil fuel costs for non-ZEVs. These energy costs are discussed in the “Net energy savings” section below, as the incremental energy impact is expected to be a net benefit to ZEV owners.

The Government of Canada is not expected to incur any additional costs beyond the need to inform stakeholders of the proposed Amendments. This is because the current regulatory framework is expected to remain the same and the existing implementation, compliance, and enforcement policies and programs would continue to apply.

Monetized (and quantified) benefits

The key benefits estimated in this analysis are the net energy savings that accrue to those who purchase ZEVs as a result of the proposed Amendments, and the reduced GHG emissions from these ZEVs which will help Canada meet its international commitments to reduce the global damages of climate change. There will also be reduced air pollution emissions, which is expected to directly benefit Canadians.

Net energy savings

ZEVs do not require traditional liquid fuels to operate (though PHEVs can use both electricity and liquid fuels), and are more energy-efficient than their non-ZEV equivalents. Consumers will, however, carry a cost to charge their electric vehicles. Energy costs associated with charging ZEVs are estimated in this analysis through the use of the Department’s E3MC model. E3MC provides projections on the increased electricity demand associated with an increase in the sale of ZEVs, as well as electricity price forecasts. As noted in the 2021 Reference Case, the price of electricity ranges across Canada, and results from E3MC reflect these regional differences. Similarly, the decrease in liquid fuels demanded due to fewer non-ZEV purchases in the regulatory scenario is also modelled using E3MC and monetized using the Reference Case’s liquid fuel price projections for blended gasoline and diesel. The liquid fuel price projections included in the Reference Case are informed by the Canadian Energy Regulator’s projections.

In present value terms, total increased electricity costs over the time frame of the analysis are estimated to be $55.8 billion. These costs are expected to be offset by the fossil fuel savings which are estimated to be $89.7 billion. It is estimated that the proposed Amendments would lead to $33.9 billion in net energy savings over the time frame of the analysis.

| Monetized energy impacts | Undiscounted — 2026 | Undiscounted — 2035 | Undiscounted — 2050 | Discounted — 2026 to 2050 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity costs | 31.3 | 2 894 | 7 394 | 55 825 |

| Fuel cost savings | (46.5) | (4 613) | (12 024) | (89 730) |

| Net energy savings | (15.2) | (1 719) | (4 630) | (33 905) |

Greenhouse gas emission reductions

The proposed Amendments would contribute to Canada’s climate commitments by reducing tailpipe emissions from passenger automobiles and light trucks. BEVs produce no GHG emissions from operation, while PHEVs have reduced emissions — the model assumes they operate using their battery 65% of the time, and gasoline the other 35%. Based on these projections, it is estimated that over the time frame of the analysis (2026 to 2050), the proposed Amendments would reduce GHG emissions by approximately 430 Mt, compared to the baseline scenario.

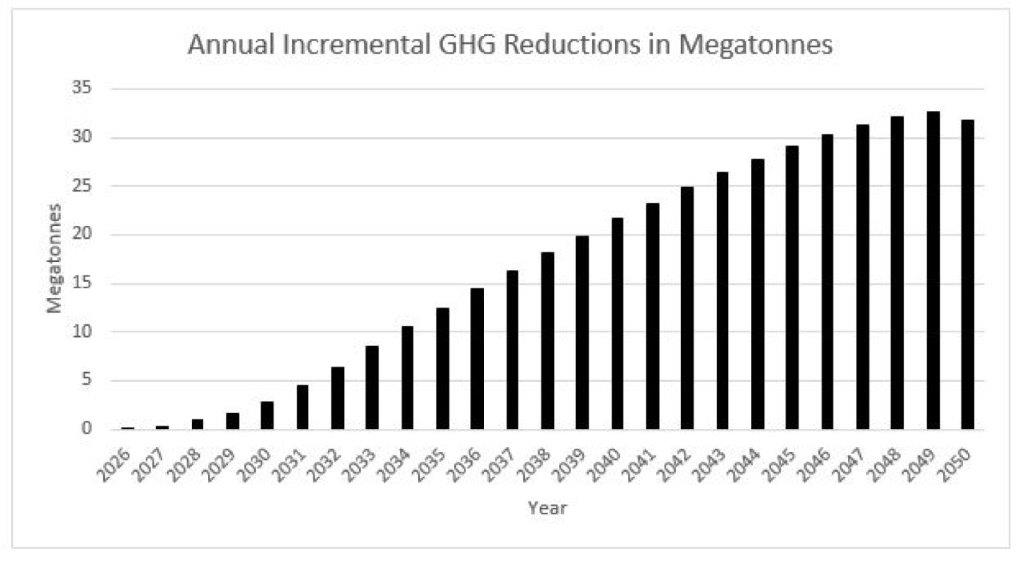

Figure 3: Annual incremental GHG reductions in megatonnes (Mt)

Figure 3: Annual incremental GHG reductions in megatonnes (Mt) - Text version

Figure 3 illustrates a bar graph, representing annual incremental GHG reductions, with the y-axis representing GHG emission reductions in megatonnes from 0 to 35 megatonnes (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent, and the x-axis representing the years from 2026 to 2050. GHG emission reductions begin near 0 in 2026, slowly increase year over year, approaching 5 Mt in 2031, and surpassing 20 Mt in 2040. GHG emission reductions continue rising until they peak in 2049 at almost 33 Mt, and then dip slightly to just under 32 Mt in 2050.

To monetize these benefits, the quantity of avoided GHG emissions each year was multiplied by the Department’s schedule of the value of the social cost of carbon (SCC), which is $59 in 2025, rising to $89 by 2050. Over the time frame of the analysis, the cumulative monetized benefits of the GHG emissions reductions from the transition to ZEVs would amount to $19.2 billion in present value terms over the 25-year timeline. Since 2016, all federal regulatory analysis involving GHG emissions has relied on SCC values published by the Department. Recent academic literature indicates that previous iterations of the models used to develop the SCC are out of date. The changes needed are largely due to (1) updates to global population, economic activity, and GHG emission estimates over time, and (2) new research on climate science and the damages caused by climate change. As a result, the current SCC values used for Canadian regulatory analysis likely underestimate climate change damages to society, and the social benefits of reducing GHG emissions. The Department is in the process of updating its SCC estimates, but results are not yet available. A recent estimate from the literature is applied in the sensitivity analysis.

Air pollution reductions

On-road vehicles are a key source of air pollution exposure. Almost half of Canadians live near high traffic roads. Individuals of low socio-economic status are more likely to live in these areas than wealthier Canadians. In addition, about 50% of schools and long-term care facilities in Canada are located near high traffic roads.footnote 18 Air pollution from on-road vehicles increases the risk of developing asthma and leukemia in children as well as lung cancer in adults.footnote 19,footnote 20 Overall, emissions from all on-road vehicles in Canada contribute to an estimated 1 200 premature deaths and millions of cases of nonfatal health outcomes annually, with a total estimated economic value of $9.5 billion annually. The emissions from light-duty vehicles specifically contribute approximately 37% of the health burden associated with air pollution from on-road vehicles.footnote 21 Children, the elderly, individuals with underlying health conditions and people living in high exposure areas are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of air pollution.

Light-duty vehicles targeted by the proposed Amendments are a significant source of air pollutant emissions, including fine particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen oxides (NOx), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), carbon monoxide (CO) and other toxic substances. These emissions also contribute to ambient levels of secondarily formed pollutants of health concern, including PM2.5 and ozone (two principal components of smog). ZEVs offer an opportunity to address traffic-related air pollution, delivering immediate and local health benefits to the Canadian population, and those benefits would accrue into the future over the lifetime of the ZEVs. The estimated reductions in select pollutants from the proposed Amendments are included in Table 5 below.

| Type of air pollutants | 2026 | 2035 | 2050 | Total — 2026 to 2050 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particulate matter (PM2.5) | <1% | 13% | 40% | 18% |

| Nitrogen oxides | <1% | 14% | 53% | 20% |

| Volatile organic compounds | <1% | 15% | 64% | 23% |

| Carbon monoxide | <1% | 18% | 70% | 27% |

Given the magnitude of these reductions, the proposed Amendments are expected to directly benefit many Canadians, including those most exposed and most vulnerable to air pollution from on-road vehicles.

Qualitative impacts

The analysis has only quantified certain impacts and monetized those most likely to contribute to the net impact in the cost-benefit analysis. Other impacts are considered qualitatively below.

Maintenance cost savings

The proposed Amendments would be expected to yield maintenance cost savings for consumers as fully electric vehicles (EVs) have fewer moving parts than non-ZEVs, do not require oil changes or engine tune-ups, and do not contain spark plugs or engine air filters that may generally require replacement. A study by the U.S. Department of Energy estimates that electric vehicle ownership results in a two-cent maintenance cost saving per kilometre driven.footnote 22

Reduced refuelling time

A survey of the literature by the National Academy of Sciences found that approximately 80% of all charging is done at home.footnote 23 Although charging a ZEV takes more time than fuelling a non-ZEV, consumers who charge overnight at home would save time from not having to stop at a gas station. Those who do not charge at home, however, would likely experience increased refuelling time as even the fastest chargers exceed the average time non-ZEVs take to fuel. This does not take into account how often one refuels their vehicle, which may be more frequent with short-range BEVs, and PHEVs which can use gasoline and electricity. Overall, it is expected that the proposed Amendments would generate some time savings for consumers.

More publicly available infrastructure

The proposed Amendments may incentivize an increase in private investment for public charging infrastructure. Direct-current fast chargers (DCFCs) can charge an EV in approximately 30 minutes;footnote 24 this is significantly longer than the average refuelling time for a non-ZEV. Various businesses may choose to capitalize on the opportunity to increase foot traffic at their establishments by investing in charging infrastructure. This increased investment in publicly available charging infrastructure would also benefit Canadian drivers as it would make ZEV chargers more readily available and conveniently located.

Rebound effect (vehicles driven more due to the benefits of lower operating costs)

The proposed Amendments would generate energy savings, some of which would be expected to be directed towards additional driving. This is known as the “rebound effect,” or the price elasticity of kilometres driven with respect to fuel cost per kilometre. Academic research from the United States evaluated light-duty vehicle travel from 1966 to 2007 and found that gasoline prices have a statistically significant impact on vehicle distance travelled.footnote 25As the electricity cost to drive a ZEV is lower than gasoline and diesel costs for a non-ZEV, consumers could drive more kilometres and still save money.

Increased congestion, accidents, and noise

As noted above, energy savings may encourage consumers to drive more — a phenomenon that is referred to as the “rebound effect.” Consequently, vehicles may spend more time on the road, which would increase the negative externalities associated with driving, such as traffic congestion, motor vehicle crashes, and noise. Although ZEVs are quieter than their non-ZEV counterparts, more vehicles on the road could lead to an increase in other vehicle-associated noise, such as honking. Not only could the additional time spent driving cause more accidents, but accidents could become more fatal. ZEVs tend to be heavier than non-ZEVs due to the weight of batteries on-board, and research shows that accident fatality increases as the weight differential between vehicles increases.footnote 26

Consumer welfare losses related to restrictions in vehicle choice and higher vehicle prices

The proposed Amendments are expected to lead to a loss of consumer choice, as the non-ZEVs, which are preferred by some, will eventually be phased out of the light-duty vehicle market. Furthermore, ZEVs are expected to generally cost more than non-ZEVs, and this vehicle price increase could lead to a reduction in the quantity of vehicles purchased. The magnitude of these consumer welfare losses is difficult to estimate, but losses are not expected to be significant, especially when factoring in how consumers value energy savings, which are estimated to be roughly twice the upfront costs of ZEVs.

Increased grid readiness

The proposed Amendments would increase the number of ZEVs on the road and, consequently, would increase the demand on the electricity grid. A significant increase in demand for electricity, particularly at peak time, could lead to an increase in electricity prices. This is not expected to be a significant issue, however, as the proposed Amendments are only projected to increase ZEV electricity demand as a percentage of overall electricity demand from 1.2% in the baseline to 2.5% in the regulatory scenario in 2035. By 2050, ZEVs electricity demand is projected to increase from 2.6% to 4.8% of overall electricity demand in Canada. Further, charging demand from a public charging lot could exceed the peak capacity of a residential feeder-circuit transformer. Investments would need to be made to increase the peak kilowatt hour load. However, the majority of charging is expected to be done overnight for the majority of consumers who invest in at-home charging equipment. A significant change in electricity pricing is therefore not expected.

Reliability of battery supply

Recently, global supply chain challenges have affected the ability of vehicle manufacturers and importers to keep up with the growing demand for ZEVs. The proposed Amendments, along with similar regulations in other jurisdictions, would further increase the demand for large-scale batteries. Should battery production and acquisition continue to be outpaced by demand for electric vehicles, this could lead to increased vehicle costs that would negatively impact consumers.

Costs of retraining mechanics

Mechanics would likely incur costs to retrofit their shops and invest in training to service ZEVs. These costs would likely be shared with consumers by passing much of the costs onto consumers through higher service costs. Additionally, mechanics may experience reduced demand as ZEV uptake increases due to the lower maintenance requirements compared to ZEVs.

Gas stations

Gas stations with attached convenience stores may lose foot traffic in their storefronts, and consequently earn less profits through the sale of both fuel and convenience goods. Gas stations who invest in the transition to charging infrastructure may maintain some of these sales; however, they will face increased competition since chargers can be installed anywhere, and many drivers are expected to charge their vehicles at home.

Summary of quantified and monetized cost-benefit analysis (CBA) results

The proposed Amendments are estimated to result in GHG emission reductions of 430 Mt over the 2026 to 2050 time frame (see annual reductions in figure 3 above). The proposed Amendments are also expected to reduce particulate matter 2.5 by an average of 18%, nitrogen oxides by 20%, volatile organic compounds by 23%, and carbon monoxide by 27% over the same time frame (see table 5 above). The value of these air quality improvements are not monetized in this analysis.

From 2026 to 2050, the proposed ZEV Amendments are estimated to have incremental ZEV and home charger costs of $24.5 billion, while saving $33.9 billion in net energy costs. These impacts accrue to those who switch to ZEVs in response to the proposed Amendments. The cumulative GHG emission reductions are estimated to be 430 Mt, valued at $19.2 billion in avoided global damages. These GHG emission reductions will help Canada meet its international GHG emission reduction obligations for 2030 and 2050. The proposed Amendments are thus estimated to have net benefits of $28.6 billion, as shown below.

Table 6: Summary of monetized costs and benefits (millions of dollars)

- Number of years: 25 (2026 to 2050)

- Dollar year for prices: 2021

- Present value year for discounting: 2023

- Social discount rate: 3% per year

| Monetized impacts | Undiscounted — 2026 | Undiscounted — 2035 | Undiscounted — 2050 | Discounted — 2026 to 2050 | Annualized |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHG benefits | 8 | 887 | 2,839 | 19,180 | 1,101 |

| Net energy savings | 15 | 1,719 | 4,630 | 33,905 | 1,947 |

| Total ZEV costs | 396 | 1,611 | 694 | 24,446 | 1,404 |

| Total net benefits (costs) | (373) | 995 | 6,774 | 28,639 | 1,645 |

The analysis estimates that the proposed Amendments would yield net benefits, but there are several modelling limitations to this analysis that could affect the estimates, particularly for GHG emission reductions.

Modelling limitations

This analysis is unable to estimate the impact of policies announced after mid-2021, when the baseline Reference Case was finalized. The one exception is the EPA Final Rule for pre-2026 model year GHG emission vehicle standards, published in late 2021, which are incorporated by reference in the Regulations and are therefore included in the 2021 Reference Case. Therefore, the regulatory scenario may attribute some of the incremental impacts to the proposed Amendments that might be expected to occur in an updated baseline scenario. Complementary policies that, for example, increase ZEV infrastructure, could increase consumer preferences for ZEVs. Further strengthening of the fleet average GHG emission standards of the Regulations would also be expected to result in firms considering adding more ZEVs to their fleet to lower their fleet average emissions, even in the absence of the proposed Amendments.

This analysis is also unable to predict whether, or to what extent, firms may partake in strategic pricing and fleet mix behaviour in response to the proposed Amendments. Where firms must comply both with a fleet average GHG emission standard, as well as a ZEV sales target, they may opt to meet their obligations under the two requirements by using increased ZEVs (which lower their fleet average GHG emissions) to offset increased sales of high profit but higher emitting non-ZEVs. This strategy would become less viable in Canada as the ZEV sales requirements increase to 100% by 2035. Further strengthening of fleet average GHG emission standards in Canada and the United States would reduce this risk.

This analysis does not estimate how consumers would respond to changing vehicle prices. Incremental ZEV manufacturing costs, which are expected to be reflected in higher vehicle prices, might change the quantity of vehicles purchased in the regulatory scenario. Firms might choose cross-pricing strategies to optimize sales, but the overall quantity of vehicles demanded would be expected to fall in response to rising vehicle prices. Previous regulatory analyses of the Regulations have not considered this impact, as it is difficult to estimate and the impacts on the cost-benefit analysis are not expected to be significant, especially when factoring in how consumers value the net energy savings associated with ZEVs.

By using E3MC to estimate annual energy and emission impacts, this analysis takes a calendar year approach to reporting results, as opposed to using an engineering model that could calculate the lifetime impacts of each year of incremental vehicle sales (model year approach). This difference in perspective leads to an undervaluation of the lifetime benefits associated with these proposed Amendments in terms of total GHG reductions and net energy savings related to ZEV operations. Given that vehicles have an estimated life expectancy of 15 years, benefits beyond the 2035 model years are underestimated.

At the same time, this analysis does not use a life cycle model that could take into account other impacts of the proposed Amendments, particularly in terms of upstream GHG emissions from increased electricity generation and decreased fossil fuel production. Nor does the analysis consider the costs that may be associated with the mining of minerals for battery production, and the end-of-life disposal of vehicles and their parts. Published studies show that relative to internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, BEVs have higher vehicle manufacturing emissions due to the emission intensity from battery production.footnote 27 Nonetheless, over the life cycle, the emissions from BEVs are estimated to be 50 to 60% lower than those of a non-ZEV (Nealer et al., 2015). Overall, this suggests that the net GHG reductions from the proposed Amendments are overvalued. However, when judged along with the underestimation of lifetime vehicle emissions, the GHG emission reduction estimate provided in the central case is likely to be reasonable.

Sensitivity analysis

The monetized results of the cost-benefit analysis are based on key parameter estimates; however, the true values of the results may be higher or lower than estimated. To account for this uncertainty, sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the effect of higher or lower parameter estimates on the estimated impacts of the proposed Amendments.

Cost of fuels: The projections for the cost of ethanol, gasoline, and diesel used in the central case comes from the Department’s E3MC model. If future realized costs of liquid fuels are higher or lower than what is projected, then fuel savings would be impacted proportionately. A sensitivity analysis was conducted that considers the impact that fuel costs that are 50% higher or lower than the projected values would have on the net effect of the proposed Amendments. The result of this analysis shows that a 50% decrease in the cost of liquid fuels would yield a net cost of the proposed Amendments equal to $16.2 billion, and a 50% increase in the cost of liquid fuels would yield a net benefit of $73.5 billion. Thus, the net benefit conclusion of the analysis is sensitive to this variable.

Cost of electricity: Similar to fuels, electricity cost projections used in the central case come from the Department’s E3MC model. The price of electricity could fluctuate due to a high strain on the electricity grid. Additionally, consumers may carry higher electricity costs due to premiums being applied to the cost of electricity at publicly available charging stations. Taking into consideration the potential for a 50% increase or decrease in projected electricity costs would lead to a range of net benefits from $0.7 to $56.6 billion. Thus, the net benefit conclusion of the analysis is not sensitive to this variable.

Charging infrastructure: The central case assumes that 80% of ZEVs are purchased with charging equipment. This assumption comes from a NAS report that presents data showing there are roughly four home chargers for every five ZEVs in the United States. It is likely that the proportion of ZEVs bought with a charger will decrease overtime as consumers begin replacing existing ZEVs as opposed to replacing non-ZEVs. This would lead to lower costs than those estimated in the central case. Alternatively, the central case does not estimate installation costs for at-home chargers, which could lead to higher costs than those estimated in the central case. A sensitivity analysis was conducted that explores the scenario where charger costs are 50% more, and 50% less than the central estimate. This would lead to a range of net benefits of $24.1 to $33.2 billion. Thus, the net benefit conclusion of the analysis is not sensitive to this variable.

Cost of zero-emission trucks: Battery electric vehicles have a finite amount of power, and any additional burden you place on the battery will pull power away from the propulsion of the vehicle and decrease its range. The central case assumes that consumers with towing needs would opt for a PHEV with a towing package and not a BEV, since the addition of a towing package on a BEV had a significantly higher manufacturing cost in comparison to that of the towing package on a PHEV. The incremental manufacturing cost difference between a BEV and a PHEV with the towing package is estimated to be roughly Can$17,100 in 2026. Thus, in the central case analysis, the BEV trucks were assumed not to contain the towing package. Adding the towing package to BEV trucks would increase the total cost of vehicles by $66.3 billion for a net cost of $37.7 billion. Thus, the net benefit conclusion of the analysis is sensitive to this variable. However, the scenario is not considered to be realistic, as a majority of truck purchasers who want the towing package would not likely prefer the much more expensive BEV towing option.

Basic cost of ZEVs: The central case employs cost estimates from CARB; however, there are various factors that may impact the future costs associated with ZEV battery production. For example, higher or faster technological advancement than is expected and economies of scale could lead to lower costs than projected. Similarly, global access to minerals could lead battery costs to increase higher than is currently projected. To account for these uncertainties, a sensitivity analysis was undertaken that considers how the net impact of the proposed Amendments may be impacted by ZEV vehicle costs that are 50% higher or lower than is used in the central case. This range in possible upfront vehicle costs would create a range of net benefits from $21.0 to $36.3 billion. Thus, the net benefit conclusion of the analysis is not sensitive to this variable.

Social cost of carbon (SCC): Canada’s current value of the SCC is under review and likely to be updated in 2023. The central analysis employs the Department’s current schedule of the SCC, which is $61/t in 2026. In September 2022, Resources for the Future published its findings from a comprehensive study, based on best evidence and practices designed to produce an updated SCC.footnote 28 The results of this research suggest that an updated SCC would be US$80 (Can$102) when using a 3% near-term discount rate. Conducting a sensitivity analysis using this value for the SCC would increase the benefits associated with the reduction in GHGs by $19.3 billion, so the net benefit conclusion is not sensitive to the SCC value.

Discount rate: Canada’s Cost-Benefit Analysis Guide for Regulatory Proposalsfootnote 29 states that a 7% real discount rate should be used for most cost-benefit analyses. For some regulatory proposals, such as those relating to human health or environmental goods and services, guidance states that it is more appropriate to employ a social discount rate. The central case reported in Table 6 employs a 3% social discount rate; however, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using the 7% real discount rate to compare estimates. The use of the higher discount rate results in an overall net present value of $10.7 billion, so the net benefit conclusion of the analysis is not sensitive to this alternate rate.

| Variable | Sensitivity analysis case | Total net present value (billions of dollars) |

|---|---|---|

| Central case (2026 to 2050) | N/A | 28.6 |

| Higher (or lower) fossil fuels prices would increase (or decrease) net energy savings. 50% lower net energy savings would yield net costs. | Higher (50%) | 73.5 |

| Lower (50%) | (16.2) | |

| Higher (or lower) electricity prices would decrease (or increase) net energy savings. | Higher (50%) | 0.7 |

| Lower (50%) | 56.6 | |

| Higher (or lower) home charging unit costs would decrease (or increase) the overall net benefits of the proposed Amendments. | Higher (50%) | 24.1 |

| Lower (50%) | 33.2 | |

| Manufacturing BEV trucks to include a towing package would increase ZEV costs and yield a net cost. | Include towing package | (37.7) |

| Higher (or lower) ZEV prices (excluding home charging infrastructure) would decrease (or increase) net benefits. | Higher (50%) | 21.0 |

| Lower (50%) | 36.3 | |

| An updated value for the social cost of carbon would increase the value of GHG emissions reductions. | Updated value | 48.0 |

| A higher discount rate would lower the present value of net benefits. | 7% | 10.7 |

In almost all the cases shown above, the analysis concludes that the proposed Amendments would still be expected to yield net benefits. There are two scenarios that show net costs: one where liquid fuel prices are 50% lower, and one where all BEV trucks are purchased with an expensive towing package. Although liquid fuel prices fluctuate, Canadian average gasoline prices have not gone below $1/L in over five years, with the exception of the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.footnote 30With increased carbon pricing and global politics contributing to higher oil prices, this level of liquid fuel price decrease is not expected to occur. For trucks requiring towing capabilities, manufacturers and importers are expected to opt to produce and import PHEVs as the incremental cost to include a towing package on a BEV truck is significantly higher and thus would be an inefficient allocation of resources. Therefore, the Department concludes that it is plausible to claim that the proposed Amendments would yield net benefits.

Strategic environmental assessment

In accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals, a strategic environmental assessment for the ZEV policy was conducted in 2018 and concluded that the proposed Amendments are in line with the objectives of the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy (FSDS). According to the 2022–2026 FSDS, these objectives include protecting Canadians from air pollution, transitioning to zero-emission vehicles, and taking action on climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Distributional analysis (including gender-based analysis plus [GBA+])

The proposed Amendments are expected to have disproportionate impacts on various subpopulations within Canada, as the costs and benefits are unlikely to be evenly distributed. The benefits of reducing GHG emissions are global in nature, and the non-monetized benefits that reductions in air quality have on specific Canadian subpopulations are discussed in the “Air pollution reductions” section. The cost-benefit analysis estimates the incremental costs and benefits of ZEV ownership, and as these impacts are not distributed evenly in society, they are further discussed below.

Household and GBA+ impacts

The proposed Amendments are expected to have a disproportionate impact on low-income households due to the higher upfront cost of ZEVs in early years and the potential for non-ZEV costs to increase due to a decreasing supply of these vehicles in response to the increasing ZEV sales targets. In the short term, this would likely make it hard for low-income households to acquire ZEVs. As a result, in the early years, potentially only those in a financial position to afford the relatively higher upfront cost of purchasing a ZEV would benefit from a total cost of ownership that is lower than that of an equivalent non-ZEV vehicle. This is largely the result of missing out on the fuel savings afforded by owning a ZEV. It is expected that, over time, ZEVs would become more affordable, with BEV cars expected to become as cost-effective as non-ZEVs in the early 2030s.

Low-income households are also more likely to live in rental units, which in some cases may not be suitable for at-home charging equipment. This indicates that low-income households that do purchase ZEVs would be more likely to have to rely on publicly available charging stations that may charge a premium on the cost of electricity. These factors indicate that low-income households would likely be disproportionately and negatively affected by the proposed Amendments.

The proposed Amendments would also disproportionately impact households living in rural and northern communities that may have lower access to public charging infrastructure. In addition, northern communities are expected to face more difficulties with the transition to ZEVs due to prolonged periods of cold temperatures that may affect the range of battery-powered electric vehicles. Furthermore, electricity costs vary by region, thus Canadians living in regions with high electricity costs may not benefit from energy savings as much as those living in lower-cost areas.

Some Canadians may experience a compounding effect of disproportionate impacts if there is an intersectional component where individuals belong to both regional and economic subgroups discussed above. To mitigate these impacts and ensure a just transition, the Government and its partners would continue to work on policies to ensure that ZEVs are accessible to individuals despite economic or regional differences and that the charging infrastructure needs of all Canadians can be met.

As noted in the “Monetized (and quantified) impacts” section, the proposed Amendments are expected to reduce air pollutants, resulting in a positive impact for most Canadians. These impacts may be felt more by Canadians who are at higher risk of being negatively impacted by air pollutants — namely children, the elderly, individuals with underlying health conditions, and people living in high traffic exposure areas.

Competitiveness analysis

The proposed Amendments are in alignment with similar regulatory ZEV sales targets in British Columbia and Quebec, as well as California and 15 other U.S. states, known as the section 177 states. Manufacturers and importers of light-duty vehicles have already responded to the regulatory requirements in other jurisdictions, and it is expected that they would similarly adapt to these proposed Amendments. The addition of the proposed Amendments to the Canadian-American market would represent an increase from 36% of the market having ZEV regulations to 42% having them. The competitiveness of Canadian manufacturers and importers is not expected to be impacted by these proposed Amendments, as profit-seeking firms are expected to adopt sales strategies for regional markets as they have done for certain states and Canadian provinces, and pass on any incurred costs to the consumers in the form of prices.

Small business lens

The current Regulations already include provisions specifically designed to reduce the compliance burden on small businesses. These provisions temporarily allow companies that manufacture or import a total volume of light-duty vehicles that is less than a prescribed threshold to elect to comply with less stringent standards up to and including model year 2016. In addition, the fleet average CO2e emission standards (GHG standards) do not apply to any companies that manufacture or import, on average, fewer than 750 new light-duty vehicles in Canada per year. This threshold does not apply to the proposed Amendments implementing ZEV sales targets, which offer no exemptions. The proposed Amendments to establish annual ZEV sales targets would, however, have a compliance option for companies to buy excess credits from other companies and they would have an alternative flexibility option to create credits by contributing to a designated ZEV activity. Currently, there are no regulatees that fall within the threshold of being a small business. As a result, the small business lens would not apply to the proposed Amendments.

One-for-one rule

The one-for-one rule applies since there is an incremental increase in administrative burden on business, and the proposal is considered an “in” under the rule. Under the proposed Amendments, manufacturers and importers of new light-duty vehicles would be subject to mandatory requirements that prescribe annual proportions of vehicles offered for sale that must be ZEVs. The administrative costs borne by manufacturers and importers of LDVs that would result from the proposed Amendments are tied to learning about the amendments, compiling records, and conducting business associated with trading credits and creating credits by contributing to ZEV activities. The one-for-one analysis estimates that 19 manufacturers and importers would bear incremental costs in relation to the proposed Amendments. The net annualized costs are estimated to be $24,500, or $985 per business.footnote 31

Regulatory cooperation and alignment

The proposed LDV ZEV sales targets are in line with the proposed rules in British Columbia,footnote 32 Quebecfootnote 33 and California,footnote 34 all of which have set a target to achieve 100% ZEV sales by 2035. As of 2026, it is expected that California’s ZEV regulation will have been adopted across 15 other U.S. states, otherwise known as section 177 states, collectively representing almost 36% of the U.S. market.footnote 35 In addition, the U.S. administration has set a policy goal for 50% of new vehicle sales to be ZEVs by 2030footnote 36 and is expected to use post-2026 GHG emission standards to help meet these targets. The U.S. EPA is expected to publish a Notice of Proposed Rule Making for post-2026 GHG emission standards in March 2023.