Vol. 145, No. 23 — November 9, 2011

Registration

SOR/2011-233 October 27, 2011

SPECIES AT RISK ACT

Order Amending Schedule 1 to the Species at Risk Act

P.C. 2011-1264 October 27, 2011

His Excellency the Governor General in Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of the Environment, pursuant to subsection 27(1) of the Species at Risk Act (see footnote a), hereby makes the annexed Order Amending Schedule 1 to the Species at Risk Act.

ORDER AMENDING SCHEDULE 1 TO THE SPECIES AT RISK ACT

AMENDMENT

1. Part 4 of Schedule 1 to the Species at Risk Act (see footnote 1) is amended by adding the following in alphabetical order under the heading “MAMMALS”:

Bear, Polar (Ursus maritimus)

Ours blanc

COMING INTO FORCE

2. This Order comes into force on the day on which it is registered.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Order.)

Executive summary

Issue: The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) has assessed the Polar Bear as a species of special concern. COSEWIC is a committee of experts that assesses wildlife species in Canada and designates which are at risk. It provides species assessments to the Minister of the Environment in order for him to make recommendations to the Governor in Council (GIC) as to listing on Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA).

Description: This Order, on the recommendation of the Minister of the Environment, adds the Polar Bear species to Schedule 1 of SARA as a species of special concern. Under SARA, the listing of a species as special concern in Schedule 1 requires the preparation of a management plan to prevent listed species from becoming endangered or threatened.

Cost-benefit statement: The key prohibitions of SARA do not apply to species listed as special concern; therefore, the incremental impacts of this Order are expected to be low.

This Order is an important commitment regarding Polar Bears and their vulnerability, and sets in motion the development of a long-term management plan within three years from the time the Polar Bear is listed. To the extent that the Order contributes to the protection of the species, the economic evidence presented regarding passive and active values from Polar Bear preservation indicates that the regulatory action is likely to result in net benefits to Canadians.

Consultation: Environment Canada carried out extensive public consultations regarding the listing of the Polar Bear under SARA between November 2008 and March 2010. In the North, the majority of communities contacted were not in favour of listing the Polar Bear. While many people in the communities feel climate change is affecting Polar Bears, they also observed that wildlife populations normally fluctuate and move, and that Polar Bears are very adaptable. Many people report the population to be increasing rather than decreasing and that the Polar Bears are appearing in different places, particularly in the communities, such that there are strong concerns for public safety. There were also strong feelings that the research is not conclusive, particularly as the surveys are too limited and too infrequent. In the Western Arctic, unanimous support was received for the decision to list the Polar Bear as a species of special concern from all Inuvialuit communities consulted. In the southern part of Canada, the vast majority of comments received indicated support for listing.

Business and consumer impacts: The impacts of listing on governments, industries and individuals are expected to be low due to the limited management actions required by listing Polar Bears as a species of special concern as well as to their limited distribution and overlap with human activities. In addition, the Polar Bear already receives protection under various statutes of Parliament and provincial and territorial acts (e.g. Ontario’s Endangered Species Act).

Domestic and international coordination and cooperation: Since 1973, international Polar Bear management has been coordinated under the Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears signed by Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Norway, the United States and Russia (hereinafter “the Agreement”). The Agreement provides protection of Polar Bear habitat and its populations. The signatory countries — Canada, the United States, Denmark (Greenland), Norway and Russia — allow harvesting of Polar Bears by local Aboriginal peoples who are exercising their traditional rights. Canada has also signed agreements with the United States and Greenland for the joint management of shared Polar Bear subpopulations.

Within Canada, the management of Polar Bears falls under the authority of the following levels of government: the federal government, four provinces (Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador), three territories (Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut) and five wildlife management boards established as part of the settlement of land claims. Hunting is managed primarily through quotas while protecting the rights of Aboriginal peoples.

Performance measurement and evaluation plan: Environment Canada has put in place a Results-based Management and Accountability Framework (RMAF) and Risk-based Audit Framework (RBAF) for the Species at Risk Program. The specific measurable outcomes for the program and the performance measurement and evaluation strategy are described in the Species at Risk Program RMAF-RBAF. The program evaluation is scheduled for 2011–2012.

Issue

A growing number of wildlife species in Canada face threats that put them at risk of extirpation or extinction. Canada’s natural heritage is an integral part of Canada’s national identity and history. Wildlife, in all its forms, has value in and of itself and is valued by Canadians for aesthetic, cultural, spiritual, recreational, educational, historical, economic, medical, ecological and scientific reasons. Canadian wildlife species and ecosystems are also part of the world’s heritage and the Government of Canada has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Conservation of Biological Diversity. The Government of Canada is committed to conserving biological diversity.

Polar Bear populations are at risk of becoming threatened in 4 of the 13 Canadian subpopulations (i.e. Western Hudson Bay, Southern Beaufort Sea, Kane Basin and Baffin Bay), likely due to climate change or over-harvesting. (see footnote 2) Overall, COSEWIC has assessed the Polar Bear as a species of special concern at the national level to prevent it from becoming threatened or endangered. COSEWIC is an independent committee of experts that assesses and designates which wildlife species are at risk in Canada. A species assessment was provided to the Minister of the Environment. The Minister then indicated in the Species at Risk Public Registry how he would respond to the assessment and provided timelines for action. The assessment was then forwarded to the GIC. With this Order, the Minister of the Environment is making a recommendation to the GIC to add the Polar Bear to Schedule 1 of SARA.

Management and conservation of Polar Bear in Canada

A key milestone in Polar Bear conservation was the signing of the 1973 international Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears. (see footnote 3) The Agreement provides protection of Polar Bear habitat and its populations. The signatory countries — Canada, the United States, Denmark (Greenland), Norway and Russia — allow harvesting of Polar Bears by local Aboriginal peoples who are exercising their traditional rights.

While several of the signatory countries (e.g. the United States and Norway) consider Polar Bears marine mammals, in Canada, they are considered terrestrial mammals. (see footnote 4) Therefore, Canadian provincial and territorial governments that are responsible for the management of terrestrial species are also responsible for the management of Polar Bears. Where Polar Bears are found on federal lands (e.g. national parks), the federal government is responsible for their management. Polar Bears in national parks are managed and protected under the CanadaNational Parks Act by protecting its habitat within federal park boundaries, while those found in national wildlife areas are managed under the Canada Wildlife Act. In the territories, wildlife management boards (WMBs), established under land claims agreements (LCAs), manage wildlife resources, which include Polar Bears.

Range of Polar Bear

Canada is home to approximately 60% of the world’s Polar Bear population and they are found in ice-covered regions from the Yukon and the Bering Sea in the West to Newfoundland and Labrador in the East and from northern Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, to southern James Bay, including coastal northern Ontario and Quebec. The Polar Bears are found mainly in the coastal regions of the Arctic Ocean.

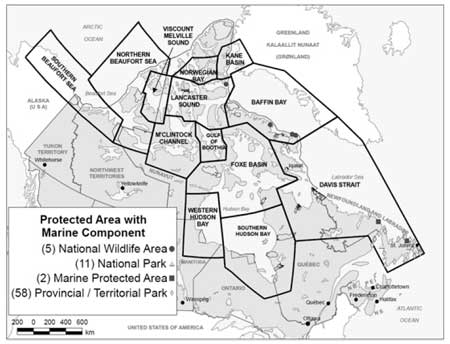

Canada’s national, provincial and territorial parks and national and marine wildlife areas where Polar Bears are found include

- 2 national wildlife areas (Baffin Bay and Lancaster Sound subpopulations);

- 11 national parks (established in 7 different Polar Bear subpopulations);

- 2 marine protected areas (found in Newfoundland and Labrador in the Davis Strait subpopulation); and

- 58 provincial and territorial parks (Southern Hudson Bay, Foxe Basin and Davis Strait subpopulations).

Management

Management and research activities for Canadian Polar Bear populations are coordinated and reviewed annually by the Polar Bear Administrative Committee (PBAC) in collaboration with the Polar Bear Technical Committee (PBTC). The PBAC members are senior managers representing territorial, provincial and federal governments, WMBs and key Aboriginal organizations. The PBTC membership includes federal scientists, provincial and territorial biologists, university specialists and U.S. (Alaska) researchers.

Figure 1 illustrates Canadian Polar Bear subpopulations and protected areas.

Figure 1: Canadian Polar Bear subpopulations and protected areas

Source: Environment Canada, “Maps of Global and Canadian Sub-populations of Polar Bears and Protected Areas,” www.ec.gc.ca/nature/default.asp?lang=En&n=F77294A3-1#pb_pa (accessed August 3, 2010).

In Canada, the management authority for the hunting of Polar Bears rests with provinces, territories and WMBs that have authority by virtue of land claim agreements. Hunting is largely managed through quota systems and according to land claims agreements. In some jurisdictions, as part of subsistence hunt provisions of land claims agreements, a limited sport hunt is allowed within quotas. Sport hunters are guided by Aboriginal peoples who harvest by traditional means. In most parts of Canada, the management of the harvest is done in accordance with sound conservation practices based on the best available scientific data and traditional knowledge. (see footnote 5)

Every year, the Canadian PBTC collates, discusses and presents Polar Bear harvest information. Each responsible government on PBTC and PBAC works in collaboration with Aboriginal peoples in their jurisdiction under land claim agreements to set harvest limits, distribute hunting tags and identify research priorities.

In most cases, the various management authorities determine total allowable harvest by assessing local population changes. The rate of harvest is at a level that enables the population to reach a target management objective. Annual quotas for Polar Bear harvest from each subpopulation are set by territorial or provincial governments and by WMBs as provided for in land claims agreements (LCAs). After being divided among jurisdictions, the total allowable harvest is generally divided further among local communities within jurisdictions. Each jurisdiction-management board, however, retains the right to set its own harvest limits independently. As seen below, harvest management differs among the provinces and territories.

Table 1: Provincial/territorial legislation that affects Polar Bear management

|

Province/Territory |

Legislation |

Legislation application |

Aboriginal harvest rights |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Northwest Territories |

Northwest Territories Wildlife Act and the Species at Risk Act |

Prohibits hunting prescribed unless in compliance with described provisions or with a licence. Outfitted hunts for non-residents are included in the quota system. There is currently no listing under the N.W.T. Species at Risk Act. |

Polar Bear harvest is controlled by a quota system. As per the relevant LCAs, WMBs provide decisions for habitat and wildlife management to the Minister who then either accepts or disallows the decision. |

|

Nunavut |

Nunavut Wildlife Act and the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act |

There is no species list under the Nunavut Wildlife Act. |

Polar Bear harvest is controlled by a quota system. As per the relevant LCAs, WMBs provide decisions for habitat and wildlife management to the Minister who then either accepts or disallows the decision. |

|

Manitoba |

The Endangered Species Act of Manitoba (MB ESA); reclassified threatened 2008 |

Currently designated as threatened under the MB ESA; prohibits killing, injuring, and disturbing species, and destroying, disturbing or interfering with habitat, including removal of a resource upon which the species depends. Habitat includes land, water and air. Polar Bears may only be killed in defence of life or property. |

As defined in the MB ESA, Status Indians may not hunt any protected wildlife for which all hunting is prohibited, including Polar Bears. |

|

Newfoundland and Labrador |

Newfoundland and Labrador Endangered Species Act |

The Polar Bear is listed as vulnerable under the Newfoundland and Labrador Endangered Species Act. This designation requires the development of a management plan and it allows for the development of additional regulations for the protection of Polar Bears, if deemed necessary for conservation purposes. |

Polar Bear harvest is controlled by a quota system. As per relevant LCAs, WMBs provide decisions for habitat and wildlife management to the Minister who then either accepts or disallows the decision. |

|

Ontario |

Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, 1997 (FWCA) Polar Bear Protection Act, 2003 (PBPA) Ontario Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ON ESA) |

The FWCA prohibits hunting of Polar Bears except to Aboriginal peoples. The PBPA ensures humane treatment of Polar Bears. The Polar Bear is a threatened species in Ontario (2009). A recovery strategy will be finalized by September 2011 in accordance with the ON ESA. |

Only First Nations hunters who are Treaty 9 members residing along the Hudson Bay and James Bay coast can legally harvest Polar Bears. There is a permissible kill of no more than 30 Polar Bears per year that is controlled by restricting the annual sale of hides under a trapper’s licence to those hides with an official seal attached by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. |

|

Quebec |

An Act respecting threatened or vulnerable species and the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement |

Listed as vulnerable in Quebec. |

Under the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, Nunavik Inuit, Crees and Naskapis are allocated a “guaranteed harvest” of 62 Polar Bears annually, subject to conservation limitations. There is no quota system. |

|

Yukon |

Yukon Wildlife Act, 1981 |

The Polar Bear is listed as a species of special concern under the Yukon Wildlife Act. Through a land claim agreement, the Inuvialuit of the western Arctic have the exclusive right to harvest Polar Bears. |

Polar Bear harvest is controlled by a quota system. WMBs provide its decision for habitat and wildlife management to the Minister who then either accepts or disallows the decision. |

Source: Environment Canada internal document

Table 2 contains the status of Polar Bear subpopulations in Canada. The actual number of Polar Bears harvested is often less than the allowable limits, and has been reasonably stable since the early 1990s. For example, in 2008, the quota was 695 and the number of Polar Bears killed was 506. (see footnote 6) Tags from unsuccessful sport hunts cannot be re-entered into the system.

Table 2: Status of subpopulations of Polar Bears within or shared by Canada (see footnote 7)

|

Population |

Current Abundance Estimate (2008) |

Actual Date of Estimate |

Polar Bears/yr (Permitted Harvest)* |

2002–07 Average Kill (Polar Bears/yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Western Hudson Bay |

935 |

2005 |

Nunavut 46 + Manitoba |

46.8 |

|

Southern Hudson Bay |

681 |

2005 |

Nunavut 25 + Ontario and Quebec |

36.2 |

|

Foxe Basin |

2 300 |

2004 |

Nunavut 106 + Quebec |

98.6 |

|

Lancaster Sound |

2 541 |

1998 |

Nunavut 85 |

82.4 |

|

Baffin Bay |

1 546 |

2004 |

Nunavut 105 + Greenland |

232.4** |

|

Norwegian Bay |

190 |

1998 |

Nunavut 4 |

3 |

|

Kane Basin |

164 |

1998 |

Nunavut 5 + Greenland |

12.8 |

|

Davis Strait |

2 251 |

2006 |

Nunavut 52 + Greenland and Quebec |

60 |

|

Gulf of Boothia |

1 528 |

2000 |

Nunavut 74 |

56.4 |

|

M’Clintock Channel |

284 |

2000 |

Nunavut 3 |

1.8 |

|

Viscount Melville Sound |

215 |

1996 |

Nunavut 7 |

4.8 |

|

Northern Beaufort Sea |

1 200 |

2006 |

Nunavut 65 |

34.4 |

|

Southern Beaufort Sea |

1 526 |

2006 |

Nunavut 81 |

53.4 |

* The identified permitted harvest includes the maximum harvest that is presently (2007–08) allowed by jurisdictions with an identified quota plus what is taken by non-quota jurisdictions.

** Prior to 2006, the harvest of Polar Bears from the Kane Basin and Baffin Bay subpopulations by Greenland was considerable. However, rates decreased precipitously following the introduction of a Canada-Greenland quota system in 2006. In 2003–04, Greenland harvested 164 Polar Bears and Nunavut harvested 72, whereas in 2006–07, Greenland harvested 75 and Nunavut, 99 Polar Bears. This decrease, coupled with a scheduled decrease by Nunavut of 10 Polar Bears per year over the next four years, will drop the combined harvest to approximately 125 Polar Bears which is a significant step towards ensuring sustainability.

International considerations

Conservation of Polar Bears requires international cooperation. Under Article II of the Agreement, all parties agree to “take appropriate action to protect the ecosystems of which Polar Bears are a part, with special attention to habitat components such as denning and feeding sites and migration patterns, and shall manage Polar Bear populations in accordance with sound conservation practices based on the best available scientific data.” (see footnote 8)

In 2006, the Polar Bear was up-listed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list from lower risk to a vulnerable category, meaning that, as a species, it faces a higher risk in the wild. (see footnote 9)

The Polar Bear is also listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES). (see footnote 10) According to CITES, Polar Bears are not necessarily threatened or endangered but require controlled trade in order to prevent population decline. In Canada, the management responsibility for the establishment and allocation of harvest quotas for Polar Bear lies with the provincial and territorial governments. For the most part, actions have been taken to ensure the harvest within all Canadian Polar Bear subpopulations is sustainable, and take into account current information on subpopulation status. Canada has determined that international export of Polar Bear is considered non-detrimental, on the condition that there is no export from the Baffin Bay subpopulation.

United States

In the United States, the Polar Bear is a federally protected species under the Marine Mammal Protection Actof 1972. In addition, on May 15, 2008, the Polar Bear was listed as threatened under the United States’ Endangered Species Act (U.S. ESA). Regulations prohibit hunting of Polar Bears by non-aboriginal hunters and establish special conditions for the import of Polar Bears or their parts and products into the United States. Alaska’s Native peoples remain allowed to harvest some Polar Bears for subsistence purposes. (see footnote 11)

Canada

In Canada, current management of the Polar Bear harvest is consistent with the Agreement. In addition, Canada has been an active supporter of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature/Species Survival Commission, Polar Bear Specialist Group, since its formation in 1968.

In the past few decades, Canada has signed the following agreements on the management of Polar Bears:

- In 1988, the Inupiat of the United States and the Inuvialuit of Canada signed an agreement for management of the shared Southern Beaufort Sea subpopulation.

- In 2008, a Memorandum of Understanding between Environment Canada and the United States Department of the Interior for the Conservation and Management of Shared Polar Bear Populations was signed to collaborate on Polar Bear issues, to further the consideration of Aboriginal traditional knowledge, and to promote consistent methods for Polar Bear population modeling, data capture and research.

- In 2009, a Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of Canada, the Government of Nunavut, and the Government of Greenland for the Conservation and Management of Polar Bear Populations was signed to provide a framework for the cooperative management, including the coordination of recommendations for hunting quotas, of the shared Polar Bear populations of Kane Basin and Baffin Bay.

Objectives

The purposes of SARA are to prevent wildlife species from becoming extirpated or extinct, to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity, and to manage species of special concern to prevent them from becoming endangered or threatened. SARA established COSEWIC as an independent scientific body to provide the Minister of the Environment with assessments of the status of Canadian wildlife species that are potentially at risk.

The purpose of this Order is to add the Polar Bear to Schedule 1 as a species of special concern. This amendment is made on the recommendation of the Minister of the Environment on the basis of the COSEWIC assessment, which is carried out using the best available information on the biological status of a species, including scientific knowledge, community knowledge and Aboriginal traditional knowledge, and on consultations with governments, Aboriginal peoples, stakeholders and the Canadian public.

Description

On February 3, 2011, the GIC acknowledged receipt of the Polar Bear assessment from COSEWIC. COSEWIC is a committee of experts that assesses and designates which wildlife species are in some danger of disappearing from Canada. Information relating to COSEWIC can be found at their Web site at www.cosewic.gc.ca.

COSEWIC has assessed the Polar Bear as a species of special concern. Below is the COSEWIC reason for designation.

Reason for designation

“The species is an apex predator adapted to hunting seals on the sea ice and is highly sensitive to over harvest. Although there are some genetic differences among Polar Bears from different parts of the Arctic, movement and genetic data support a single designatable unit in Canada. It is useful, however, to report trends by subpopulation because harvest rates, threats, and, hence, predicted population viability, vary substantially over the species’ range. Some subpopulations are over harvested and current management mostly seeks the maximum sustainable harvest, which may cause declines if population monitoring is inadequate. Until 2006, some shared subpopulations were subject to harvest in Greenland that was not based on quotas. Population models project that 4 of 13 subpopulations (including approximately 28% of 15,500 Polar Bears in Canada) have a high risk of declining by 30% or more over the next 3 Polar Bear generations (36 years). Declines are partly attributed to climate change for Western Hudson Bay and Southern Beaufort Sea, but are mostly due to unsustainable harvest in Kane Basin and Baffin Bay. Seven subpopulations (about 43% of the total population) are projected to be stable or increasing. Trends currently cannot be projected for 2 subpopulations (29% of the total population). Polar Bears in some subpopulations show declining body condition and changes in denning location linked to decreased availability of sea ice. For most subpopulations with repeated censuses, data suggest a slight increase in the last 10–25 years. All estimates of current population growth rates are based on currently available data and do not account for the possible effects of climate change. The species cannot persist without seasonal sea ice. Continuing decline in seasonal availability of sea ice makes it likely that a range contraction will occur in parts of the species range. Decreasing ice thickness in parts of the High Arctic may provide better habitat for the Polar Bears. Although there is uncertainty over the overall impact of climate change on the species’ distribution and numbers, considerable concern exists over the future of this species in Canada.” (see footnote 12)

Under section 65 of SARA, upon listing on Schedule 1, wildlife species classified as special concern are subject to the preparation of a management plan. Management plans must be prepared and posted on the SARA Registry within three years from the time a species is listed. The plan must include measures for the conservation of the species and their habitat. If the Minister of the Environment is of the opinion that an existing plan relating to the Polar Bear includes adequate measures for the conservation of the species, he/she can adopt the existing plan in its entirety or incorporate any part of it into a SARA-compliant management plan for the species.

Regulatory and non-regulatory options considered

As required in SARA, once COSEWIC submits assessments of the status of the species to the Minister of the Environment, there are only regulatory options available.

COSEWIC meets twice annually to review information collected on wildlife species and assigns each wildlife species to one of seven categories: extinct, extirpated, endangered, threatened, special concern, data deficient, or not at risk. It provides the Minister of the Environment with assessments of the status of wildlife species, and reasons for the designations. The Minister must then indicate how he will respond to each of the assessments and, to the extent possible, provide timelines for action. A response statement is then prepared, in consultation with Parks Canada Agency where the terrestrial species is found on lands administered by that Agency, and posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry within the required 90-day timeline.

The Minister of the Environment then forwards the COSEWIC assessments to the GIC. Following public consultation, the Minister of the Environment will then make a recommendation to the GIC on whether or not a species should be added to Schedule 1 of SARA or whether the matter should be referred back to COSEWIC for further information or consideration.

The first option, to add the species to Schedule 1 of SARA, will ensure that a wildlife species receives protection in accordance with the provisions of SARA including mandatory recovery or management planning, as the case may be.

The second option is not to add the species to Schedule 1. Although the species would benefit neither from prohibitions afforded by SARA nor from the recovery or management activities required under SARA, species may still be protected under other federal, provincial or territorial legislation or Aboriginal laws as established under Land Claims and Self-government Agreements. When deciding to not add a species to Schedule 1, it is not referred back to COSEWIC for further information or consideration. COSEWIC reassesses species once every 10 years or at any time it has reason to believe that the status of a species has changed.

The third option is to refer the assessment back to COSEWIC for further information or consideration. It would be appropriate to send an assessment back if, for example, significant new information became available after the species had been assessed by COSEWIC.

For more details about the listing process, please refer to www.sararegistry.gc.ca.

Benefits and costs

Economic evidence of Polar Bear values to Canadians

The Polar Bear is of great significance to Canadians and is especially important spiritually, culturally and economically to Northern Aboriginal peoples. (see footnote 13) Specifically, the species is valued in traditional ways of life within Northern communities and plays an important role in Aboriginal culture. No animal holds as visible or significant a place in Canadian Inuit culture as the Polar Bear. (see footnote 14)

Canadians value the Arctic and its natural environment. According to a recent poll regarding the most important issue facing the Arctic region of Canada, 33% of Northern Canadian respondents and 39% of Southern Canadian respondents see the environment as the most important Arctic issue. (see footnote 15)

Protecting species at risk can provide numerous benefits to Canadians beyond the direct economic revenues. Various studies indicate that Canadians place value on preserving species for future generations to enjoy, and derive value from knowing the species exist. (see footnote 16) Furthermore, the unique characteristics and evolutionary histories of many species may also be of special value to the scientific community.

Benefits and costs of this Order will mostly be accrued in the future after the management plan has been consulted on, developed and implemented. Therefore, this analysis is limited in scope and attempts to quantify values associated with the economic value of the species and to discuss distributional impacts.

A summary of the qualitative analysis of socio-economic impacts is presented in Table 3 at the end of the “benefits and costs” section.

The economy of the Northern territories, where most of the Polar Bear range is found, represents a mixed economy model, featuring both land-based and wage economies. The Polar Bear has been economically important to Aboriginal communities of the North, whether harvested for subsistence or sport hunt. Aboriginal people have been hunting the Polar Bear for millennia for food and clothing, as well as for spiritual and cultural reasons.

The concept of Total Economic Value (TEV) (see footnote 17) represents all values to society derived from an environmental asset such as a species at risk. It includes benefits that can be observed in the market and non-market values which contribute to the well-being of society. The TEV of a Polar Bear can be broken down into active and passive values.

Active (use) values include

- Direct use — such as subsistence including sport hunting; and

- Indirect use — such as observation of a species in the wild or in a zoo, scientific value.

Passive (non-use) values include

- Bequest value — altruistic value of preserving a species for future generations; and

- Existence value — altruistic value that represents the value individuals derive from simply knowing that a given species exists, regardless of the potential for any future use. (see footnote 18)

Active values

The land-based economy or non-wage economy covers a number of activities, including subsistence hunting, fishing and trapping, arts and crafts, etc.

Subsistence hunting

The Polar Bear remains an important and integral part of the Inuit subsistence system. (see footnote 19) Traditionally, the Inuit have been harvesting Polar Bears for their meat and pelts. The number of Polar Bears harvested is based on a quota system.

Approximately 534 Polar Bears are harvested annually in Canada. The majority of the harvest is taken by the Inuit in Nunavut (about 325). (see footnote 20)

The process of procuring, preparing and consuming traditional foods has important social and cultural significance and is an integral part of Inuit identity. (see footnote 21)

The Inuit operate in a common-pool distribution food system where meat is distributed across the community in a non-commercial manner as there is no market for the sale of Polar Bear meat. The meat is used by the community as a source of nutritional value. Up to 200 kg of edible meat can be obtained from a large animal. (see footnote 22) The value can be calculated using the value of substitute meat found in local stores and has been estimated at $662–$1,010 (see footnote 23) per Polar Bear hunted and represents the total value of $245,545–$374,635 for Canada (see footnote 24) for subsistence hunting in Canada.

Pelts are used by Aboriginal people to produce clothing and rugs. Claws and teeth are used in traditional crafts. Pelts can also be sold at auction to generate cash revenue for a community. In 2006, the price for a single pelt was approximately $600. However, since then, a high increase in pelt values has been observed. In 2009, pelts sold for an average price of $5,300 and the total value of pelts sold was estimated at approximately $1.16 million that year for the subsistence hunt in Canada. The most recent data (January 2011) from a fur auction house indicates that the Polar Bear pelts reached an average price of $5,600, and the highest price paid was $9,800. Most of the buyers at the auction house were from Russia and China. (see footnote 25)

It is important to note that subsistence hunts represent more to Native communities than economic value. Traditional subsistence hunting is a way of life in the North, and Polar Bears are possibly the most prestigious game for the Inuit. Furthermore, the process of procuring, preparing and consuming traditional foods has important social and cultural significance, and is an integral part of Inuit identity. (see footnote 26) These values go beyond economic valuation and cannot be expressed using conventional economic techniques.

Sport hunting

Polar Bears were hunted by the Inuit long before the arrival of settlers. In the early 1800s, the Polar Bear had been sporadically hunted by whalers and its hides entered the market via the trading posts in the North creating a demand for pelts. Polar Bear hides, an important by-product of the hunt, contributed to trading for firearms and other tools essential for subsistence. The harvest of Polar Bears by Aboriginal peoples increased rapidly through the 1960s along with the transformation of the Northern economy from subsistence based to an open-market system. The trigger point was the introduction of modern equipment and technologies, which created a growing demand for goods, such as snowmobiles. The trade for the hides picked up in the 1980s when the seal skin market collapsed. (see footnote 27)

Setting harvest quotas falls under the purview of the provincial and territorial governments and the WMBs that are established through land claim agreements. Pursuant to those agreements, Aboriginal peoples in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut may choose to transfer their right (harvest allocation) to a trophy hunter, typically through selling a tag to a local outfitter. A tag may have a value of up to $2,900. (see footnote 28) This Polar Bear sport hunt represents a value of approximately $1.3 million, (see footnote 29)with $373,450 for the Northwest Territories and $923,800 for Nunavut. At an individual community level, sport hunts can represent up to 13% of a community’s total revenue. (see footnote 30) For example, according to the 2007 Polar Bear Hunter Survey, the average total estimated trip expenditures of a U.S. trophy hunter in the Northwest Territories (2007) amounted to approximately $37,000. (see footnote 31)

Even though sport hunts generate greater benefits to the community in monetary terms, the Inuit prefer to keep the majority of allocated tags for the community. Only about 20% of tags in Nunavut are allocated to sport hunters. (see footnote 32)

Arts and crafts

The production of arts and crafts is a natural complement to harvesting. Arts and crafts are produced using products derived from Polar Bear hunts, and their sales help provide the income necessary to participate in harvesting (e.g. gas for snowmobiles, ammunition, etc.). Also, the Polar Bear is often an inspiration to Aboriginal artists, and as such is an important part of the Aboriginal culture. Although for a long time the Inuit art has played an expressive role in the Inuit culture, today, many families use art making as a supplement to their family’s income. (see footnote 33)

Observation in the wild

Polar Bear ecotourism, particularly photography, has been growing since the 1970s. (see footnote 34) Today, many Canadian and U.S. private companies offer Polar Bear viewing expeditions.

Prices for Polar Bear safaris range between $3,850 and $9,130 (see footnote 35) per person, depending on length of stay and type of activities included in the package. Generally, a five-day package includes accommodation, round-trip transportation, local tours and government tax. Gratuities, museum and parks fees, extra provincial taxes, and insurance are not usually included in the packages.

The Polar Bear ecotourism industry is concentrated in Churchill, Manitoba, which is often referred to as the Polar Bear capital of the world. The economic value associated with Polar Bear viewing in its natural habitat is estimated at $7.2 million (see footnote 36) for Canada.

Scientific research

The Polar Bear has also become the subject of intense scientific research in the North, as the species is placed at the top of the food chain and often serves as an indicator of the changes in Northern ecosystems.

Passive values

Beyond the conventional “use-values” described above, people derive satisfaction and perceive benefits from knowing that the species still exists (existence value) or will exist in the future (bequest value). (see footnote 37)

With respect to species at risk, passive values tend to typically dominate all values. Even if a given species is not readily accessible to society, existence value may be the most significant or the only known benefit of a particular species. (see footnote 38)

Information on passive values is typically collected via contingent valuation studies. (see footnote 39) A review of the research to date indicates that no such studies currently exist on the Polar Bear. Based on evidence derived from other relevant contingent valuation studies, (see footnote 40) the benefit transfer technique was applied by ÉcoRessources to infer the value that Canadians would place on the preservation of this species in Canada. This value was estimated at $508 per household per year, totalling $6 billion annually for Canada. (see footnote 41) In comparison, the annual value per household of other popular species such as the humpback whale is estimated at $276, (see footnote 42)and the bald eagle would be valued up to $403. (see footnote 43)

A willingness to pay for the protection of Polar Bear habitat can also be an indicator of co-benefits associated with the protection of Polar Bears. For example, in Alaska, the willingness to pay for preserving wildlife habitat, which includes Polar Bear habitat, was estimated at between $36 and $70 per household per year. (see footnote 44)

Benefits

The Order is an important commitment regarding Polar Bears and their vulnerability, and it sets in motion the development of a management plan within three years of this listing; the incremental economic impacts of the Order are therefore low.

Although most of the benefits are likely to accrue once the management plan is implemented, listing of the species under SARA as a species of special concern raises awareness of the importance of the species and contributes to reducing further degradation of the species population due to the conservation measures contained in a management plan.

In addition to the benefits from passive values that accrue to all Canadians from the species’ preservation, sustaining a healthy population level ensures continued access to the species as a traditional resource and results in cultural, economic, and health benefits to the communities of the North.

To the extent that the Order contributes to the protection of the species, the economic evidence presented in the value to Canadians section above indicates that this regulatory action is likely to result in net benefits to Canadians.

Costs

Under SARA, when a wildlife species is listed as a species of special concern, the competent minister must prepare a management plan for the species and its habitat. (see footnote 45) To the extent possible, the management plan must be prepared in cooperation with appropriate provincial and territorial organizations, including the WMBs, and every Aboriginal organization that the competent minister considers will be directly affected. Also, prior to the implementation of the plan, consultations must be conducted with stakeholders affected by the management plan (see footnote 46) across the geographic area of the species’ occurrence.

Listing the Polar Bear as a species of special concern under SARA triggers the development of a management plan within a three-year timeframe as provided for under section 68 of SARA. As the analysis presented here considers only the incremental impacts of the Order, further analysis is needed to evaluate specific costs and benefits of the management plan. There are 13 Polar Bear sub-populations in Canada. Each sub-population is managed and monitored separately and a federal management plan may consider the needs of each sub-population on a separate basis, as well as the costs and benefits, when the plan is developed.

For a species listed as special concern under SARA, the general prohibitions do not apply, meaning there would be no immediate associated costs with listing. Rather, the affected stakeholders may incur costs that would stem from the future development and implementation of a management plan.

A guiding principle of SARA is the spirit of cooperation between all levels of government, the public and the stakeholders and, therefore, the management plan requires cooperation of various stakeholders who may incur costs arising from the Polar Bear management plan.

Distributional impacts analysis

Although the Order will not impose any new prohibitions on economic activities surrounding the Polar Bear and its direct and indirect uses (e.g. hunting, wildlife observation, mining), the measures contained in the future management plan may have potential impacts. The extent to which these measures may affect stakeholders is not fully known at this time and will need to be re-evaluated during the development of the Polar Bear management plan. However, it is important to understand who these stakeholders are and the level of economic activities involved. As most of the economic benefits derived from the direct and indirect uses described above are captured locally, it is useful to examine the stakeholders involved in the main economic activities related to the Polar Bear in the North.

Aboriginal hunters

The level of harvest allocation depends on the annual quota and is based on a combination of factors, including conservation measures, the health of the Polar Bear population in question, scientific knowledge, and traditional knowledge. Aboriginal people make up the majority of the population in the Northern Arctic (e.g. 85% in Nunavut and 50% in the Northwest Territories) and hunting is a way of life for many Aboriginal peoples. About 80% of Inuit are involved in harvesting of the wildlife. (see footnote 47) Hunting is culturally and economically important. Subsistence hunting provides traditional country food for the Inuit, material for clothing and nutrition for dogs, and generates revenues from the sales of pelts and crafts. In economic terms, it is estimated that the combined value of pelts and meat for the year 2009 was $1.46 million (see footnote 48) for the aboriginal hunters’ community.

At present, Polar Bear sport hunting is allowed only in the Northwest Territories and in Nunavut, under strict conditions of using only traditional means and conducted by local Inuit as guides and dog handlers. The majority of guides and assistants obtain a proportion of their annual cash income from their involvement with sport hunting (between $4,500 and $6,000 per hunt) (see footnote 49) which may represent a significant portion of annual income given limited employment opportunities in the North. For example, in the Nunavut Clyde River community where the average income in 2008 was $17,200, (see footnote 50) a guide could earn $6,000 per hunt. The Clyde River community of 800 inhabitants (390 hunters) hosted 10 trophy hunts that year (out of the overall quota of 45), so the access to cash through sport hunting is limited and is not available for every hunter. In addition to a wage, gratuities from satisfied clients provide on average an additional $1,100 to $2,300 per hunt. (see footnote 51) Some trophy hunters reward guides and hunt assistants with expensive and useful gifts, including rifles, binoculars, and hunting bows and arrows. In some communities, local outfitters also pay cash bonuses to the best guides and assistants. In addition to economic gains, there are important cultural and traditional elements, including community pride and the skills needed to pursue a hunt.

Hunting package wholesalers

A Polar Bear sport hunt is negotiated through a wholesaler who is typically located in Southern Canada and is responsible for the recruitment of clients. The dynamic between the wholesaler and outfitters (see footnote 52) varies and reflects the value of services provided. The wholesaler retains on average 40% to 45% of the total package value.

Local outfitters

Local outfitters receive on average 55% to 60% of the total wholesaler package price. For the 2011 season, the price for a hunting package in Nunavut varies from $20,000 to $30,000. (see footnote 53)

In addition, local outfitters can also receive payments for the community’s goods and services (e.g. payments to the Hunters and Trappers Organization [HTO]). Outfitters can also be engaged in facilitating purchasing Inuit artifacts.

Trophy hunters’ community

Canada is the only country offering a Polar Bear trophy hunt, thus attracting big game hunters from Canada and abroad. The majority of trophy hunt clientele come to the Northwest Territories and Nunavut from the United States (59%) and the European Union (22%). (see footnote 54) Canadian trophy hunters are responsible for approximately 7% of all Polar Bears killed in trophy hunts. (see footnote 55) However, since the 2008 listing of the Polar Bear as a threatened species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, the number of hunters has declined due to the ban on importation of Polar Bear hides and trophies to the United States. (see footnote 56)

Territorial governments

In the Northwest Territories, the tag fee for non-resident alien hunting (i.e. U.S. or other individuals residing outside of Canada) is $100 and the Polar Bear trophy fee is $1,500. (see footnote 57) As of 2010, the fees in Nunavut were $50 for a tag and $750 for a trophy for non-resident hunters. (see footnote 58) Tag fees must be paid before a hunter goes hunting and trophy fees must be paid before the animal, or any part of it, is exported from the territory where it is hunted.

The table below describes all stakeholders and impacts in qualitative terms.

Table 3: Polar Bear impacts statement by activities (qualitative)

|

Activities |

Scope of impacts |

|---|---|

|

Subsistence hunting of Polar Bear and traditional way of life |

None — No change to harvesting allocation as a result of listing. |

|

Enhanced viewing opportunities with species recovery |

Unknown scope and scale — It is possible that the listing would increase the awareness of species status and result in enhanced tourism traffic in the area where Polar Bear viewing is accessible (e.g. Churchill, Manitoba). |

|

Commercial/sport hunting of Polar Bear |

None — No change to harvesting numbers as a result of listing. |

|

Land-use and development: Land-use for settlement |

None — No impact expected at the listing stage. However, some measures may be taken at the management plan stage in order to limit human encounters with Polar Bears (e.g. safety measures may be considered in future land development plans). |

|

Land-use and development: Industrial activities |

None — No immediate change to land-uses or industrial activities. The impacts, if known, would be taken into consideration in the development of a management plan. |

|

Existence and bequest value: Cultural and spiritual importance for communities |

Low — Bequest and existence values associated with the species would be maintained and potentially expand over time once the required management plan is implemented. |

|

Consultations, species management, monitoring |

Low — Costs will be attributed to the development of a management plan and the consultation phase. No enforcement cost (no SARA prohibitions associated with listing). |

|

Scientific understanding: Co-benefits |

None — No impact expected at listing stage. Potential co-benefits for other species may result from protecting Polar Bear habitat and research opportunities in the North, once the management plan is implemented. |

Net benefit

The key prohibitions of SARA do not apply to species listed as special concern. Therefore, the incremental economic impacts of the Order would be low.

While most of the benefits and costs occur once the management plan is developed and implemented, the Order is an important commitment regarding Polar Bears and their vulnerability, and it sets in motion the development of a long term management plan within three years from the time it is listed.

To the extent that the Order contributes to the protection of the species, the economic evidence presented indicates that the regulatory action is likely to result in a net benefit to Canadians.

Conclusion

Listing the Polar Bear under SARA represents an important step towards fulfilling SARA’s commitment to reduce the risk of the species becoming threatened or endangered. A management plan will be developed with affected parties within three years of this listing decision.

The impacts of listing on governments, industries and individuals are expected to be limited under this Order due to a combination of factors, including SARA’s designation and conservation measures already in place stemming from provincial, territorial and/or federal legislation and international commitments. The listing decision does not affect Aboriginal peoples’ ability to harvest Polar Bears.

Consultation

Under SARA, the scientific assessment of species’ status and the decision to place a species on the legal list are comprised of two distinct processes. This separation guarantees that scientists may work independently when making assessments of the biological status of wildlife species and that Canadians have the opportunity to participate in the decision-making process in determining whether or not species will be listed under SARA.

Environment Canada initiated public consultations for the proposed listing of the Polar Bear as a species of special concern on November 25, 2008. The first step was to post the Minister’s response statement to the COSEWIC species assessment on the SARA public registry. (see footnote 59) A response statement is a communications document that identifies how the Minister of the Environment intends to respond to the assessment of a wildlife species by COSEWIC. In the response statement, the then-minister of the Environment stated that he intended to make a recommendation to the Governor in Council that the Polar Bear be added to Schedule 1 as special concern. Prior to presenting the recommendation to the Governor in Council, the Minister of the Environment indicated his intention to undertake consultations with the governments of Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut, the Yukon Fish and Wildlife Management Board, the Gwich’in Renewable Resources Board, the Wildlife Management Advisory Council (Northwest Territories), the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, the Hunting, Fishing and Trapping Coordinating Committee, the Wildlife Management Advisory Council (North Slope), the Torngat Wildlife and Plants Co-Management Board, Aboriginal peoples, stakeholders, and the public.

On December 5, 2008, stakeholders and the general public were also consulted by means of a document entitled Consultation on Amending the List of Species under the Species at Risk Act: Terrestrial Species, January 2009. (see footnote 60) This consultation document, posted on the SARA Public Registry, outlined the Polar Bear and 20 other terrestrial species proposed for addition or reclassification to Schedule 1 by COSEWIC, the reasons for considering listing, and the implications of listing the species. The process also consisted of distribution of the discussion document and direct consultation with approximately 1 500 identified stakeholders, including various industrial sectors, provincial and territorial governments, federal departments and agencies, Aboriginal organizations, wildlife management boards, resource users, landowners and environmental non-government organizations. Members of the public were also provided with an opportunity to comment through the Public Registry posting.

Six comments were received from these consultations. Five of these were in favour of listing the Polar Bear and one was a general comment on the listing process.

Given the iconic status of the Polar Bear in society and its cultural value to Aboriginal peoples in the Arctic, extensive consultations with Aboriginal communities and organizations were also undertaken. These followed the processes required by existing land claims agreements. Additional time was given for these consultations in order to ensure Northern residents would have the opportunity to discuss how listing the Polar Bear on Schedule 1 of SARA would impact their lives and hunting rights. As such, the Minister of the Environment consulted extensively with the relevant boards and Northern communities in Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, the Yukon, Quebec, Manitoba, Ontario, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

In 2009, the Minister hosted a national round table in Winnipeg that brought together experts who have a role in management and/or conservation of Canada’s Polar Bears in order to hear views regarding priority areas for action and to increase awareness of the various conservation activities underway.

Engagement of Aboriginal peoples of the Arctic who play a significant role in the management of the Polar Bear was of particular importance. As required under SARA, and in accordance with certain land claims agreements which are constitutionally recognized documents, WMBs that are established under land claims agreements and are authorized by the agreements to perform Polar Bear management functions had to be consulted and a formal decision-making process followed. The consultations and the decision-making process have been successfully concluded.

A breakdown of the Aboriginal consultations by province and territory is provided below.

Nunavut

Nunavut, with a population of 35 000 residents, is home to 12 of the 13 Polar Bear subpopulations. Given the importance of the Polar Bear to Inuit in Nunavut, an invitation was extended to meet with all the Aboriginal communities, the HTOs, and the Regional Wildlife Organizations (RWO). In addition, all Nunavut residents were given an opportunity to submit comments in writing. In-person meetings were held in 23 of 25 communities and 793 people attended. One community, Baker Lake, declined and arrangements for an in-person meeting in Bathurst Inlet were unsuccessful. Of the 119 comments received, the majority did not support listing the Polar Bear under SARA. Comments received suggested that the Polar Bear is an adaptable species and it would be able to cope with climate change, that the Polar Bear population is increasing not decreasing, that the Inuit are capable of managing the Polar Bear, that the government should listen more to the Inuit, that scientists and the Inuit should work together, and that quotas should be increased.

Of the HTOs consulted, 13 did not support the proposed listing, one was in support, and one was neutral. One RWO did not support the listing and 17 members of the public sent written comments that were not in support and 2 members of the public wrote in support.

The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (NLCA) includes a decision-making process that provides for the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board (NWMB) to approve the designation of rare, threatened and endangered species in Nunavut. In 2008, a memorandum of understanding (MOU) was signed between the federal government and the NWMB. The MOU, although not legally binding, serves to harmonize SARA’s decision-making process for the listing of wildlife species with the decision-making process of the NLCA. The NWMB has formally advised the Minister of the Environment that it does not support listing the Polar Bear as a species of special concern. The NWMB’s position reflects that of the communities in Nunavut. It believes the Polar Bear population as a whole is healthy, and it is increasing in numbers in most subpopulations, even with a decrease in available sea ice.

Northwest Territories

In the Northwest Territories, six Inuvialuit communities were consulted through in-person meetings in conjunction with the local Hunters and Trappers Committee. Sixty-three people attended the meetings and 199 comments were received. The majority of comments received supported listing; however, there was concern expressed that Aboriginal traditional knowledge was not used in preparing the COSEWIC assessment and more was required. Other comments were general, relating to Polar Bear management, listing and the impacts of climate change. All six Inuvialuit communities supported listing. The Wildlife Management Advisory Council (Northwest Territories), the Inuvialuit Game Council and all the hunters and trappers committees formally wrote in support of listing the Polar Bear as a species of special concern. Three members of the public who wrote were not in support, two others wrote in support, and one was indifferent.

Yukon

The Polar Bear’s presence in the Yukon is limited to the coastal portion of the North Slope, which is contained within the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. The Inuvialuit presence in the Yukon is seasonal, and is primarily comprised of residents of Aklavik and Inuvik, located in the Northwest Territories. These two communities were consulted as part of the Northwest Territories consultative process. Both WMBs in the Yukon were consulted. The Wildlife Management Advisory Council (North Slope) indicated it was in support of listing, while the other board did not respond.

Manitoba

In Manitoba, four Hudson Bay coastal First Nations communities and the Town of Churchill were asked to participate in consultations. Each community was contacted by letter and by phone to determine their interest in being consulted on the proposed listing of the Polar Bear as a species of special concern. One community, Tadoule Lake — Sayisi Dene First Nation, declined a visit. The remaining communities indicated their interest in participating in the consultation process through in-person meetings.

At the meetings and through other consultative methods (e.g. meeting follow-up, submission of response forms to Environment Canada or to the band office and a presentation to high school students), 57 people provided 61 comments and all supported listing the Polar Bear. The main comments included concern that the Polar Bear population has not decreased in this area, that the Inuit have a right to hunt and should be kept informed on Polar Bear conservation, that Aboriginal peoples and the Province need to work together, and that climate change is the main threat for the Polar Bear, but there are other factors as well (e.g. pollution and the accumulation of environmental contaminants in fatty tissue). In addition to the 57 people who provided comments in person at the meetings, comments were also received from 3 First Nations councils, 2 members of the public, and from the Wapusk National Park Management Board who all wrote letters in support of the proposed listing.

Ontario

In Ontario, five Northern Cree communities were approached and meetings were scheduled with four of the communities. Two of the community meetings were cancelled and two others rescheduled due to an outbreak of H1N1 flu. Thirty-four people gave 63 comments during the consultation period, and support for listing and not listing was divided evenly. Other comments were indifferent, because many Cree do not hunt Polar Bears. In Fort Severn, where one of the meetings was cancelled, an elder met with Environment Canada. Subsequently, the council for the community wrote a letter indicating it was not in support of the listing. In Weenusk, the Chief met with Environment Canada officials and later wrote a letter supporting the listing. Comments received indicated that if listing as special concern would restrict the Inuit hunters, then they would oppose listing. Other comments noted increased numbers of Polar Bears, a need for Aboriginal traditional knowledge and that scientists should work with the Inuit. Overall, a full range of comments were provided during the course of the consultations; some felt it should be listed and generally supported the conservation of Polar Bears, while others felt it should not be listed, as they felt the species did not require conservation. Others shared that they did not have a lot of history with Polar Bears, and see them rarely so they cannot “support” or “not support” listing as a species of special concern. The communities did not provide an official response to list or not list the species.

Quebec

In Quebec, 74 people attended in-person meetings held in eight Inuit communities in Northern Quebec. Six communities were not in support of the listing, one community was in support, and one was undecided. Fifty-two comments were received at the in-person meetings and also through written responses. The majority were opposed to the listing. Reasons given include that communities already have management plans in place, that community safety is essential, and that if a Polar Bear is threatening a community, it may be necessary to kill it. Comments also recommended removing quotas, as they are not part of the Inuit culture and species are managed at a community level. Three organizations were also consulted. A decision-making process was followed with the Nunavik Marine Region Wildlife Board (NMRWB) that decided against the listing of the Polar Bear. The Minister rejected the NMRWB’s decision. The NMRWB recognizes that climate change will have some impact on the Polar Bear population, but believes that, in light of the increased number of Polar Bears sighted by Inuit hunters in Nunavik and other regions, listing the species under SARA is unwarranted at this time. Concern about the threat to Inuit and their property is mounting throughout Nunavik as more Polar Bears are entering communities and outpost camps. Population estimates and survival rates are dated for many subpopulations and aspects of Polar Bear adaptability to changing ice conditions are largely unknown. The NMRWB believes that updated population estimates and research on Polar Bear adaptability are needed prior to listing. The Hunting, Fishing and Trapping Coordinating Committee (HFTCC) presented two different recommendations regarding the proposed listing from the Inuit members and the Cree members: the Inuit members did not support the proposed listing while the Cree members supported the proposed listing. The Cree peoples chose to be represented by the HFTCC and did not write in separately. The Naskapi do not hunt Polar Bear, and have not expressed a position on this subject. The greatest concern for the Inuit members was the safety of their communities, as Polar Bears shift their hunting increasingly towards coastal and terrestrial ecosystems. Concerns were also expressed that management should reflect the subpopulation status and be considered and applied while taking distinct regional characteristics into account. There were concerns about the consequences of the listing to the rights and responsibilities of the Inuit and, to some extent, to the Cree as well with respect to Polar Bear hunting. The other member parties of the HFTCC are sympathetic to the special concern status. One of the primary reasons for this perspective is that they believe such a status will facilitate the collection of additional harvesting, ecological and population data on the Polar Bear in the changing environment of northern Quebec, which is a matter of concern and interest to all member parties of the HFTCC.

Newfoundland and Labrador

In Labrador, meetings were held in five Nunatsiavut communities where Polar Bear hunting takes place. Consultations were also held with three Nunatsiavut organizations. Collectively, 134 comments were received, which were equally in support and not in support of listing the Polar Bear. It was suggested that the Davis Strait Polar Bear population has increased, and some believe that it is not endangered and therefore should not be listed. They also believe there should be an increase in the hunting/harvest quota. Some of those in support of listing indicated that there is evidence of climate change occurring and this is a good reason to list the Polar Bear.

Other extended consultation feedback

Consultations were open to all stakeholders during the consultation period in the North, and a large number of comments were received. Over 3 000 letters in support of the proposed listing were sent to the Minister of the Environment, written primarily by people living outside of the Arctic Circle. Of the letters received, approximately 90% were in support of a SARA listing for the Polar Bear. Sixty per cent were received from addresses in Canada, 29% from addresses in the United States, 6% from other countries and 5% were of unknown origin. The majority of these letters indicated support based upon one or more of the following:

- The importance of granting the Polar Bear legal protection by listing it under SARA;

- The need to control or end hunting to protect Polar Bears; and

- The linkages between climate change and the protection of Polar Bears.

International

The Minister of the Environment did not hold specific international public consultations on the proposed listing of the Polar Bear under SARA. However, Environment Canada did undertake significant international communication efforts regarding the Polar Bear and CITES. The Polar Bear is listed in CITES, Appendix II, which means that international trade is monitored. Leading up to the CITES’ 15th Conference of the Parties (COP 15) in the spring of 2010, the United States government formally proposed to move the Polar Bear from Appendix II to Appendix I. An Appendix I listing would have resulted in the end of international commercial trade in any Polar Bear parts or products. Environment Canada, in consultation with northern Aboriginal communities and WMBs, disagreed with the proposed change. At COP 15, the proposal was rejected by the required two-thirds majority vote and the Polar Bear remains on Appendix II, with monitored trade continuing.

In the context of the United States CITES proposal, Environment Canada received over 60 000 letters from individuals in favour of including the Polar Bear in Appendix I. This was as a result of a letter-writing campaign that was initiated by the non-governmental organization Defenders of Wildlife. The vast majority of these letters were form letters that came from residents of the United States while some came from Canada, some from European countries, and some from Asia. This campaign is still active (see footnote 61) and CITES staff continues to receive email letters from the public on this topic.

Feedback received following publication of the proposed Order

Following the publication in the Canada Gazette, Part Ⅰ, of the proposed Order to list the Polar Bear as a species of special concern under SARA, a 30-day consultation period was open to all stakeholders and the public from July 2 to August 1, 2011.

Over 1 900 comments were received, written primarily by people living outside of the Polar Bear’s range. Approximately 99% of writers supported a SARA listing for the Polar Bear. Sixty-seven per cent of letters came from addresses in Canada, 24% from the United States and 9% from other countries. The majority of these comments indicated that Canada, which is home to 60% of the world’s Polar Bears, has a responsibility to protect their future. The Minister of the Environment is urged to put in place a management plan sooner than the mandated three-year deadline to ensure that the Polar Bear does not become threatened or endangered, and the comments point out that climate and ice habitat change in the Arctic is the primary threat to Polar Bears. Fast action on climate change is encouraged to save the Polar Bears’ habitat.

Polar Bear populations are already carefully managed collaboratively by all Canadian jurisdictions in which they are found, and by the federal government. Although the final contents of the management plan are not yet known, it will be prepared a quickly as possible and is expected to build on activities already in place.

Approximately 1% of respondents in favour also indicated personal experience behind their reasons for support as they had travelled or worked in the Arctic or were educators or authors involved with conservation and wildlife issues. An additional 1% of respondents requested that hunting of Polar Bears not be allowed.

The Polar Bear being a species of special concern, Polar Bear hunting will continue to take place under carefully controlled quota systems, as it is recognized that subsistence hunting plays an important cultural role for Aboriginal peoples.

Four non-governmental conservation organizations (NGOs) provided comments. One, based in Canada, supported the special concern listing. Three United States-based NGOs, with international membership and supporters including Canadians, suggested that COSEWIC should have assessed the Polar Bear as endangered. They state that the COSEWIC assessment did not adequately consider sea ice projections that, if factored with Polar Bear population dynamics, could be modeled to show declines, qualifying the species for endangered status. They say that COSEWIC did not adequately consider the use of designatable units in its assessment, and the listing proposal does not incorporate new information that has become available since the time of the COSEWIC assessment and that would likely have resulted in a risk assessment higher than special concern.

The Government of Nunavut’s Minister of Environment as well as the Director of Wildlife Management advised that the Government of Nunavut does not support listing the Polar Bear under SARA because it is premature to base a listing decision on ice cover predictions or models that may or may not materialize and that the Canadian Polar Bear populations are already effectively monitored and managed. Therefore, a SARA listing is unwarranted. They advised that while some areas of Polar Bear habitat may decline, others may improve, and Polar Bears are adaptable and have persisted through previous warm periods. They also advise that Inuit have intimate knowledge of Polar Bears and their life cycles and have observed an increase in their numbers.

The Polar Bear was assessed by COSEWIC as a species of special concern in 2008 based on its 2008 updated status report. COSEWIC members impartially evaluate the scientific information provided in the status report and must have majority agreement on accepting the status recommendation. A SARA listing decision must be based on the assessment provided by COSEWIC, which in turn must base its assessment on the best available information at the time of the assessment. COSEWIC based its conclusion on both scientific knowledge and traditional knowledge. This included knowledge informing the make-up of subpopulations and whether assessment by designatable units should be considered.

Overall, the special concern designation is appropriate in the face of uncertainty over ice cover projections, climate change and the present and future impact on Polar Bears. The question of whether or not Polar Bears can adapt their movements and feeding habitats to compensate for changes to ice cover remains uncertain. COSEWIC must reassess a species every 10 years or at any time that it has reason to believe that a species’ status has changed significantly. The COSEWIC status report and assessment is available online through the Species at Risk Public Registry at www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm.

Implementation, enforcement and service standards

Since the Polar Bear is being listed under SARA as a species of special concern, the general prohibitions do not apply. Therefore, compliance promotion and enforcement are not required nor planned. SARA requires that the Minister prepare a management plan for the Polar Bear within three years of the listing of this species. The plan will include conservation measures and be prepared in cooperation with appropriate provincial and territorial ministers, federal ministers, WMBs, Aboriginal organizations and any other person or organization considered appropriate. The plan will also be prepared in cooperation with authorized WMBs in accordance with the provisions of applicable Aboriginal land claims agreements. In addition, SARA requires consultations with landowners, lessees and others directly affected by the plan, including the government of any other country in which the species is found. As part of the SARA listing process, consultations have been conducted with affected communities in the North.

At the time of listing, timelines apply for the preparation of a management plan. The implementation of this plan may result in recommendations for further regulatory action for protection of the species. It may draw on the provisions of other acts of Parliament to provide required protection.

Contact

Mary Taylor

Director

Conservation Service Delivery and Permitting

Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment Canada

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0H3

Telephone: 819-953-9097

Footnote a

S.C. 2002, c. 29

Footnote 1

S.C. 2002, c. 29

Footnote 2

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Polar Bear in Canada.

Footnote 3

The text of the treaty is available at http://pbsg.npolar.no/en/agreements/agreement1973.html.

Footnote 4

For example, the United States Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972.

Footnote 5

Environment Canada, “Domestic Polar Bear Actions Underway,” www.ec.gc.ca/nature/default.asp?lang=En&n=9577616C-1#HM (accessed August 20, 2010).

Footnote 6

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Polar Bear in Canada, p. 31.

Footnote 7

Ibid.

Footnote 8

Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears: http://pbsg.npolar.no/en/agreements/agreement1973.html.

Footnote 9

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), “The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species,” www.iucnredlist.org (accessed August 19, 2010).

Footnote 10

Available at www.cites.org.

Footnote 11

United States Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972.

Footnote 12

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report, www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/cosewic/sr_polar_bear_0808_e.pdf.

Footnote 13

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Polar Bear in Canada, p. 51.

Footnote 14

George W. Wenzel, Sometimes Hunting Can Seem Like Business: Polar Bear Sport Hunting in Nunavut, Edmonton, Alberta, CCI Press, 2008.

Footnote 15

“Rethinking the Top of the World: Arctic Security Public Opinion Survey,” http://munkschool.utoronto.ca/files/downloads/FINAL%20Survey%20Report.pdf.

Footnote 16

K. Rollins and A. Lyke, “The Case of Diminishing Marginal Existence Values” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Vol. 36, No. 3, 1998, pp. 324–344.

Footnote 17

ÉcoRessources, “Évidences de l’importance socio-économique des ours polaires pour le Canada.”

Footnote 18

K. Wallmo, “Threatened and Endangered Species Valuation: Literature Review and Assessment,” www.st.nmfs.gov/st5/documents/bibliography/Protected_Resources_Valuation%20.pdf

#search='endangered%20species%20economic%20valuation (accessed August 26, 2010).

Footnote 19

Milton Freeman and Lee Foote, Inuit. Polar Bear and Sustainable Use.

Footnote 20

Lee Foote and George W. Wenzel, Polar Bear Conservation Hunting in Canada: Economics, Culture and Unintended Consequences, Canadian Circumpolar Institute Press.

Footnote 21

M. M. R. Wein, E. E. Freeman, and J. C. Makus, “Use of and Preference for Traditional Foods among the Belcher Island Inuit,” Arctic, Vol. 49, No. 3, 1996.

Footnote 22

M. M. R. Freeman and L. Foote (eds), Inuit, Polar Bears, and Sustainable Use: Local National and International Perspectives, CCI Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton 2009.

Footnote 23

ÉcoRessources, “Évidences de l’importance socio-économique des ours polaires pour le Canada.” All values are converted to CAN$2009.

Footnote 24

Ibid.

Footnote 25